Mike Mercer frames this week’s Principle 6 Newsletter with a passage from economist Adam Smith’s The Theory of Moral Sentiments. People’s desire to achieve a “mutual sympathy of sentiments” with others “leads [them] to develop habits, and then principles, of behavior, which come to constitute one’s conscience.”

The enlightenment period and its theories directly informed the cooperative identity. “By the mid-1800s, these concepts matured into the early principles and values of cooperative enterprise,” Mercer writes.

Read the full newsletter below, then consider how your co-op puts the cooperative identity into practice. NCBA CLUSA is on a mission to document Principle 6 collaborations across the country so we can identify trends, document best practices and share this knowledge with you—our fellow cooperators!

Share your example of Principle 6

Principle 6 Newsletter – Mutual Sympathy of Sentiments

July 27, 2022

All human knowledge derives solely from experience. Passions rather than reason govern human behavior. – “A Treatise of Human Nature,” David Hume, 1740

The feedback we receive from perceiving (or imagining) others’ judgement centers an incentive to achieve ‘mutual sympathy of sentiments’ with them and leads people to develop habits, and then principles, of behavior, which come to constitute one’s conscience. – “The Theory of Moral Sentiments,” Adam Smith, 1759

Rational self-interest and competition can lead to economic prosperity. – “The Wealth of Nations,” Adam Smith, 1776

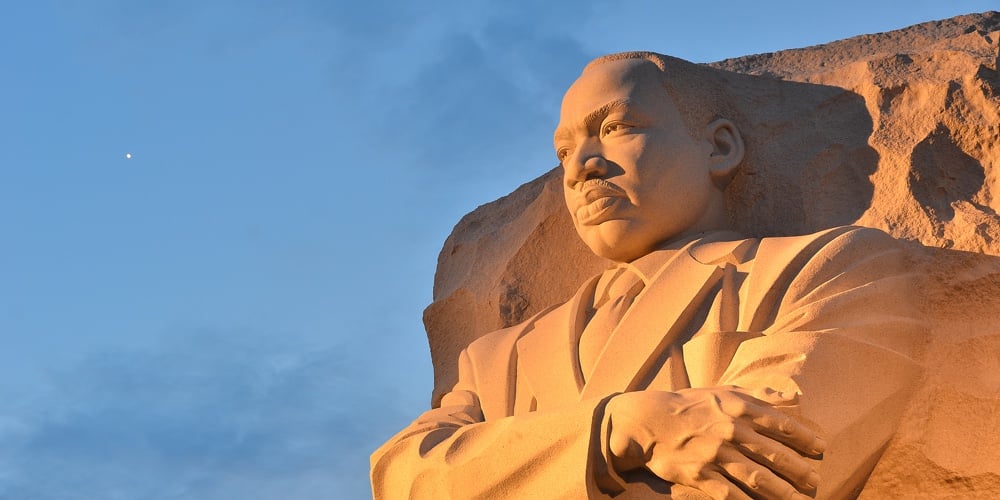

Large statues of David Hume and Adam Smith stand nearly across the street from each other in the center of Edinburgh, Scotland. They lived during the Enlightenment—the post-Medieval period of rational thought, experimentation, scientific method and (most explosively) questioning the authority of lords, monarchs and church. Hume and Smith crafted the language of individualism and sowed the seeds of “rational man” economic theory. Among other things, a rational man was viewed to act in fulfillment of individual needs/wants, accept the division of labor, acknowledge win-lose competition as a good thing and embrace the idea of freedom (of expression, mobility, worship and the like). These seeds were planted in the writings and teachings of the 1700s.

The enlightenment period and its theories created the conditions for what became known in hindsight as the Industrial Revolution. Factories brought peasants away from the field. Specialized labor and the factory processes displaced artisans. Capital displaced land as the raw material of wealth creation and accumulation. In these ways, most of the seeds planted in the late 1700s and early 1800s enabled the evolution of what we now call free-market economics. These were also the conditions that fostered revolutions in the American colonies, France and other places. Democratic principles were learned in no small part from the governance practices of the Scottish Presbyterian Church (the Kirk).

OK, nice story, but what does this have to do with co-ops?

Well, some of those seeds were planted with the DNA of Adam Smith’s early notions of “mutual sympathy of sentiments”—in his first magisterial work, The Theory of Moral Sentiments. These seeds sprouted initially as concern about the judgement of others, which evolved over time to form a conscience of mutuality. By the mid-1800s, these concepts matured into the early principles and values of cooperative enterprise.

In retrospect, it is probable that “mutual sympathies” were never imagined as passions of societal altruism. Rather, it was likely that rational men and women were acting to fulfill individual needs by coming together, pooling their resources to better compete in the increasingly ruthless win-lose economic order of the times. From this vantage point, cooperators were cut from the same individual-centric piece of cloth. Cooperators just viewed interdependence (solidarity) as a better strategy for making ends meet.

Two centuries later, in the era of the modern corporation and all of the laws/customs that go with it, in the midst of a technology/information transformation, present-day stewards of co-ops remain competitive souls at heart. The thing is that co-op leaders function with a duty to those being served, who are individually striving to advance the well-being of self. It is for this reason that a key cooperative principle centers on the idea of voluntary participation.

Hume, Smith and others of their day were provocative in their characterization of humans as having more than a small dose of self-centered aspiration. They also opined that competitive interaction of individuals freed from strict conformity with church and monarchy would lead to better economic prosperity. Whether they imagined that many individuals would voluntarily cooperate to advance their well-being is unclear. But many did. So today, co-op leaders have a responsibility to enhance cooperative benefits.

A contemporary notion of “mutual sympathy of sentiments” is this thing we call cooperative identity. And cooperative identity is the thing that separates co-ops from the organizations that grew from the The Wealth of Nations seeds of Darwinian self-interest. Co-ops do compete but they are structured to elevate cooperation to worthy virtue.

Should that mean that the most impactful co-op leaders are virtuous—in a mutual sympathy of sentiments sort of way?

Stay tuned,

Mike