For hundreds of years, co-ops have emerged alongside broader societal movements. But for U.S. credit unions today, “political neutrality—not alignment with labor, capital or protest—is the preferred posture. Sustainability through recessions and political upheaval has been the reward,” Mike Mercer writes in this week’s issue of the Principle 6 Newsletter, republished below. But what benefits of being part of a movement are they missing?

“There might be another way to look at the idea of ‘movement,’ especially for credit unions and other consumer co-ops. Not ‘movement,’ but ‘moveUPment,” Mercer adds.

Read the full issue of Principle 6 Newsletter below to find out. And while you’re thinking about “cooperation among cooperatives,” take a moment to consider how you and your cooperative practice this principle. NCBA CLUSA is on a mission to document Principle 6 collaborations across the country so we can identify trends, document best practices and share this knowledge with you—our fellow cooperators!

Share your example of Principle 6

Principle 6 Newsletter – MoveUPment

Issue 20 – April 21, 2021

“Unions [in the 1840s] responded to the industrial and corporate revolutions with the idea that a group of cooperating workers, pooling their resources…might be able to avoid having to sell themselves into wage slavery. The cooperative movement attempted to establish a permanent structural foothold in the economic system through incorporation.” – For All the People, John Curl, 2009

“Political democracy is almost universally valued in the United States, but the idea of economic democracy has been largely ignored in favor of a model that concentrates economic decision-making power in proportion to wealth. The result of this anti-democratic model during the past 40 years has been an increasing disparity between rich and poor in this country… Cooperatives are the solution to many of the major economic, social, and environmental problems in the United States today.” – The Cooperative Solution, E. G. Nadeau, 2012

“At the Platform Cooperativism conference, John Duda of the Democracy Collaborative stated that: ‘The ownership of the institutions that we depend on to live, to eat, to work is increasingly concentrated. Without democratizing our economy, we will just not have the kind of society that we want to have, or that we claim to have. We are just not going to be a democracy.’” – Uberworked and Underpaid, Trebor Scholz, 2017

The “credit union movement.”

You don’t hear that phrase too often these days. Certainly not among the cool kids. Pragmatic practitioners prefer to be part of the “credit union industry.” Association types often use the term “credit union system.” Co-op leaders on the outside refer to the “credit union sector.” Frank Luntz teaches that “words matter.” Lisa Rusczyk wrote the book, You Are What You Think.

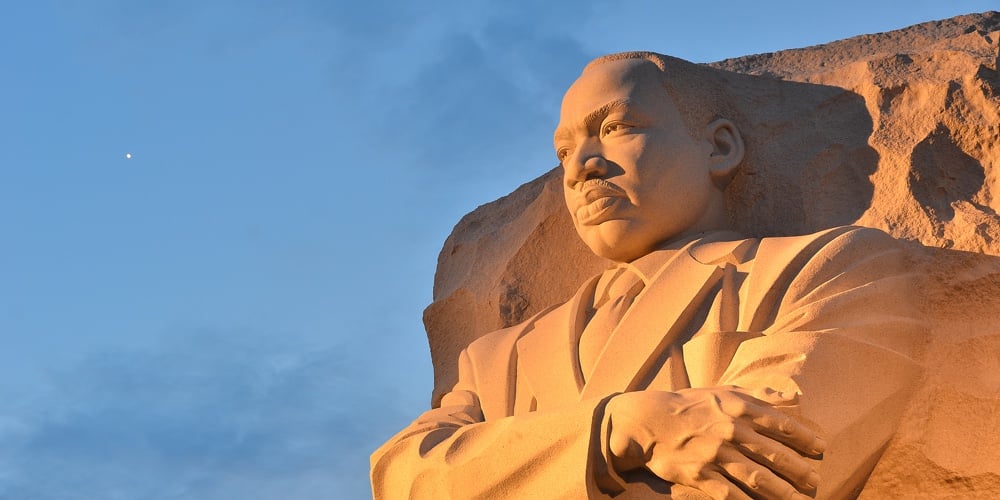

According to Wikipedia, social movements have been described as “organizational structures and strategies that may empower oppressed populations to mount effective challenges and resist the more powerful and advantaged elites.” Co-ops have long been among the organizational structures put forward as solutions by social movements throughout American history. The credit union idea took flight during a movement to mobilize worker savings and to provide a source of affordable consumer credit. To most, credit unions were a movement then. The early disciples went hither and yon without capital or even the promise of return on somebody else’s capital. The message traveled on the promise of empowerment for those who were economically oppressed (and the seduction that employers could offer a low-cost benefit).

The credit union idea took flight during a movement to mobilize worker savings and to provide a source of affordable consumer credit.

In the 1800s, family farms (long a sanctuary of independence and self-sufficiency) were rapidly coming under pressure from big agribusiness corporations that were enabled by industrialization, rail transport and oligopolistic price discrimination. A movement of mutual association quickly emerged in response. Organizations like the Grange and The Farmers Alliance were formed to leverage the political and business interests of small farmers. Their solutions included the formation of cooperative entities to support the supply and marketing needs of farmers.

The transition from farm to factory resulted in a huge demand for wage laborers. Large corporations were assembled, especially after the Civil War. It was a time when folks worked long hours, often under miserable safety conditions. It didn’t take long for the fruits of industrialization to accumulate disproportionately to the benefit of the capitalists. Workers eventually responded with the formation of labor unions that could organize work slowdowns, strikes and boycotts. When the strikes failed and workers were out of a job, one of the solutions was to form worker co-ops. In addition, the unions formed cooperative stores for the benefit of wage earners.

In the 1960s and 70s, young Americans came together in what eventually became known as the counterculture movement. Today, this movement is remembered for its experimentation with mind-altering substances, hippie gatherings, “summer of love” and Woodstock. But these people came together as a movement to oppose racial injustice, the proliferation of nuclear weapons and the war in Vietnam. The aspiration was for a better society. Once again, a movement resulted in the formation of new co-ops in food, work, and many other areas.

Today, we could be seeing the early vestiges of another movement, this time fueled by the significant transformation of work in the digital/information revolution that has enabled, among other things, the globalization of production and commerce. As before, the fruits of this transformation are quickly falling into the hands of the elite few. Platform co-ops, worker co-ops, healthcare co-ops and others are part of the solutions being put forward by leaders in this new movement.

Across 200 years of history, co-ops have been formed in concert with the societal movements that have organized to confront various forms of oppression.

Across 200 years of history, co-ops have been formed in concert with the societal movements that have organized to confront various forms of oppression. Usually thinly capitalized and often operated by well-intentioned folks without the strongest of business acumen, co-ops withered when recessions, depressions and wars came around. In addition, some co-ops struggled when the energy of the social movement waned.

Today, consumer co-ops (like credit unions) don’t talk so much about flying the flags of change or displacing capitalism. Instead, the emphasis is on things like providing honesty in the market, good pricing, and helpful advice. For U.S. credit unions, political neutrality—not alignment with labor, capital or protest—is the preferred posture. Sustainability through recessions and political upheaval has been the reward. Perhaps this explains the reluctance of large established co-ops to identify as being a movement or to overtly associate with broad social movements. Notwithstanding, societal movements (gig work or climate change action, for example) will continue to spawn new cooperative solutions.

For U.S. credit unions, political neutrality—not alignment with labor, capital or protest—is the preferred posture. Sustainability through recessions and political upheaval has been the reward.

There might be another way to look at the idea of “movement,” especially for credit unions and other consumer co-ops. Not movement, but MoveUPment. Co-ops exist to enhance the well-being of each member, in his/her unique way. They approach their work with the notion that every member is worthy. They genuinely believe that diversity is the essence of beauty. Teaching self-help is the modus operandi. Co-ops are already doing these sorts of things. Working together, co-ops could coordinate resources to surround members with a holistic economic set of solutions designed to improve their well-being. Working together, co-ops could help to organize and nurture new co-ops, adding to the catalogue of holistic solutions for members. The common cause would be moveUPment for each member. Goldman Sachs promises “moving up” to its high-roller clientele. Co-ops could do that for others in society who don’t benefit from the advice of legions of lawyers, accountants and consultants. That’s almost everybody!

Somebody call Frank Luntz…

Get us some words to embellish the concept of the “Credit Union MoveUPment.”

Better yet, think of credit unions as part of the “Cooperative MoveUPment.”

Stay tuned,

Mike