In this week’s Principle 6 newsletter, Mike Mercer ponders why worker cooperatives aren’t more prevalent in the U.S., despite opportunities like worker co-op transitions as baby boomers retire.

Read the full newsletter below, then consider how cooperatives could work together to replicate a Mondragon-style network of cooperatives in the U.S. NCBA CLUSA is on a mission to document Principle 6 collaborations across the country so we can identify trends, document best practices and share this knowledge with you—our fellow cooperators!

Share your example of Principle 6

Principle 6 Newsletter – Elevating Workers

January 11, 2023

A central question facing our economic system is whether it can provide ordinary people decently paid, meaningful work with reasonable freedom. And when the Great Recession hit, the problems surfaced together: unemployment, inadequate pay, alienation and precarity. – Juliet Schor, “After the GIG…”, 2020

Economic theory suggest that worker cooperatives are more efficient than shareholder corporations when (1) there isn’t a great deal of diversity in the levels of contribution across workers; (2) when the level of external competition is low; and (3) when there isn’t a need for frequent investments in response to technological change. – Arun Sundararajan, “Economic Barriers and Enablers of Distributed Ownership,” included in “Ours to Hack and to Own,” 2017

Worker cooperatives often exist in areas of the economy considered marginal, in which a combination of hands and minds can compensate for minimal capital. Historically, many worker cooperatives have been non-profit. This has always been typical of artisan cooperatives. – John Curl, “For All the People,” 2009

Nearly all cooperatives were formed to elevate the well-being of some targeted group of beneficiaries, usually referred to as members and legally considered to be owners. Cooperative structures were assembled to elevate the well-being of consumers. In some sectors (finance, retail and energy, for example), organic growth, collaboration and consolidation have led to considerable scale. Cooperative structures have also emerged to elevate the well-being of producers (farmers), distributors (grocers) and procurers (purchasing co-ops). Scale has also been achieved over time in these sectors.

Elevating the well-being of workers has long been among the aspirations of cooperative organizers. The idea of worker co-ops has its roots in the early days of the industrial revolution. As machines displaced artisans and the assembly line devolved work into unskilled routine, the well-being of workers became a problem in search of solution. Utopian communes and collective bargaining were among the early concepts to address the growing imbalance of power between factory owners and workers. At some point, the idea of worker ownership emerged. Democratically structured worker co-ops were among the manifestations of collective ownership that took root.

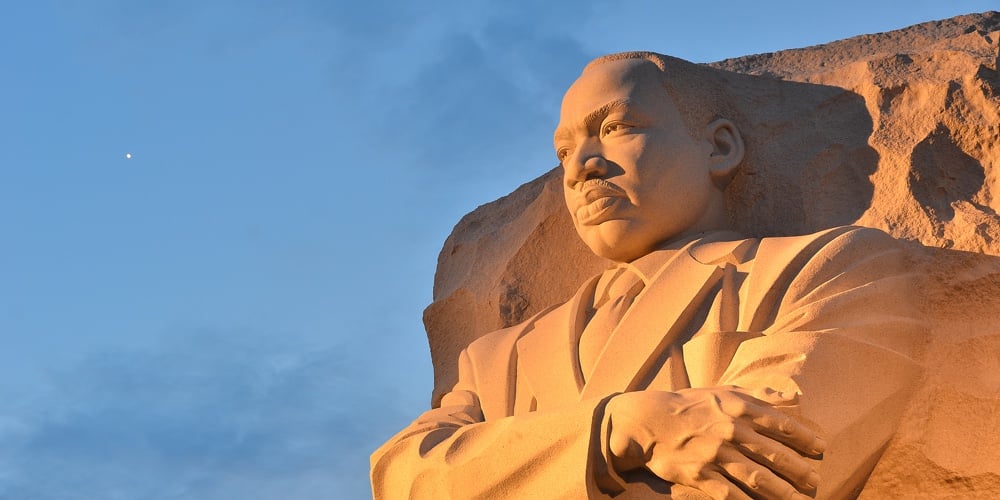

In the 1950s, a worker co-op movement was launched in a small town in northern Spain called Mondragon. Its initial form took shape as Caja Laboral Popular. Today, the Mondragon Cooperative System is the most significant example of concerted effort to elevate the well-being of workers in the world. Despite its success, it has not been replicated (a professor in Bologna says it cannot be replicated) elsewhere.

In the U.S., the number of worker co-ops is estimated to be about 1,000. And the average size of the American worker co-op is only about 10 workers. So far, worker co-ops have not had much systemic impact on worker well-being, and few (if any) can be said to have achieved significant scale. The U.S. Federation of Worker Cooperatives and the Democracy at Work Institute have compiled a directory of worker co-ops and similar democratically controlled workplaces. Together, these organizations provide technical assistance and other support services for worker co-ops. It is relatively new infrastructure; the federation was organized in 2004.

There are lots of workers in the U.S. And many of those workers feel like they have trouble getting ahead. So why aren’t there more (and larger) worker co-ops? There are likely many reasons. Consider a few…

To begin, worker ownership in the U.S. is more prevalent under the Employee Stock Option Plan (ESOP) structure. ESOPs are trust agreements, usually set up to acquire ownership of a closely held company but can also be set up as an employee benefit. Normally, ESOPs confer partial ownership to workers and do not have the same democratic governance features of a true workers co-op. There are tax benefits to the seller (of shares into the ESOP trust) and to the buyers (pre-tax contributions). According to ESOP Marketplace.com, there are 6,700-ish ESOPs with about 1.3 million participants. Recall that there are approximately 1,000 worker co-ops with just 10,000 members.

To organize a workers co-op requires the talent of one (or several) dedicated entrepreneurial-type leaders. They will need to have the means and inclination to gather support from workers to take the co-op path for organization. It is difficult to attract start-up capital for a worker co-op, either equity or debt, especially if the present owner wants to move fast to exit the business. There is help from organizations like the U.S. Federation of Worker Cooperatives, Start.coop and a few others. And there are several CDFI loan funds that are working to shorten the capital acquisition launch sequence. Hybrid worker-entrepreneur-investor structures like Obran Cooperative are also coming into play. Still, the general working population does not know much about the worker co-op option and, when they find out, are often not inclined to try.

Once a worker co-op is formed, running the shop can be difficult. In many cases, workers don’t have experience in managing a business. And using the democratic process to hire professional management can be a challenging human experience. Running a business by committee rarely works for long. Internal leadership aside, a company will need to innovate and that will require investments in new equipment or technology. Getting access to capital will not be easy along the early-stage growth path.

Especially troubling is that most closely-held business owners are making exit plans that don’t include the worker co-op option. We all read that there is tremendous opportunity for worker co-op conversions as the baby boomer generation retires. Brokers already intercede in most of the deals that come available. They are willing to pitch any buyers, especially those presenting high cash offers. And many owners would like to see their creations carry on for the benefit of the workers. But everyone is working on the clock, and few have patience for complexity.

The U.S. cooperative system does reasonably well at elevating the well-being of consumers, producers and distributors. It could do better for workers. Better circumstances for organizing and growing worker co-ops will be needed. Improvements in public policy, public awareness, technical assistance, funding and attracting entrepreneurs are just a few of the ways. The Federation is charting a course, but it will need lots of help.

The Question for this discussion: Will it be in the interest of the larger existing co-ops (and their support organizations) to help enable worker co-ops to elevate the well-being of American workers in a visible way? The “co-op” brand could be immensely strengthened. Work matters to most Americans. And co-op workers would become loyal consumers and producers, tangibly benefiting existing co-ops. Reciprocity of that sort becomes a virtuous circle. Evidence exists in northern Spain and other places around the world. But it would require long range strategic leadership and investment in the U.S.—from the cooperatives that materially elevate well-being today.

Is that even conceivable here in the U.S.?

Stay tuned,

Mike