Winter 2020

Shift Change

Could a new direction for private equity accelerate employee ownership conversions?

By Andrea Armeni and Curt Lyon

Wealth inequality continues to grow as economic gains accrue among the holders of capital rather than the providers of labor. As ownership of capital skews toward white owners, while a higher percentage of non-owning workers come from communities of color, the wealth gap will continue to exacerbate class and racial inequalities. This underscores the urgency to create asset-building opportunities at scale for workers—especially those from marginalized groups. While initiatives such as the increase of the minimum wage help provide a floor on income, more needs to be done on the ownership side.

These trends have led to a rise in interest in enterprise models that shift ownership away from traditional shareholders, such as worker cooperatives, Employee Stock Ownership Plans (ESOPs) and multi-stakeholder trust-owned companies. This is reflected in policy initiatives prioritizing employee ownership at the local, state and federal levels, which correspond with favorable public opinion of employee ownership.

Despite the momentum, the number of employee owned companies is not growing very fast. Of the two main avenues for creating more employee ownership, start-up employee-owned enterprises (generally worker cooperatives) have the advantage of employee ownership baked into their DNA from the get go. Converting conventional, established businesses to employee ownership, on the other hand, holds promise for scale, since it avoids the inherent risks of start-up businesses and builds on the existing capital of viable companies.

There is an imminent opportunity for conversions at scale based on the number of businesses that are facing succession contexts. Every day, 10,000 baby boomers retire, a generation that owns more than 50 percent of businesses in the U.S. These businesses may shut down or be absorbed into larger conglomerates, erasing jobs and economic activity from their communities and adding to corporate consolidation. Turning over ownership of these companies to their employees can preserve the business’ community commitment and provide asset-building opportunities for the workers who created the value in the first place.

Two types of conversions

There are two main options for employee ownership (EO) conversions: worker cooperatives and ESOPs. Conversions to worker cooperatives are a well-recognized opportunity, and several Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFIs), such as The Working World (TWW) and Shared Capital Cooperative, have led the way in providing financing for these deals. These transactions typically use debt financing (loans).

While a cooperative cannot sell ownership in the form of stock to non-worker investors, TWW has been an innovator in offering equity-like financing products tailored to worker cooperative conversions. These conversions, deeply rooted in solidarity movements, have historically relied on philanthropic support for financing and for the requisite technical assistance. This has helped ensure a workercentric approach, but has also historically limited the scalability of the model in terms of number of transactions as well as size.

Can the successes and innovations of worker cooperative conversions help inform other transactions that may not share their limitations? There is promise in ESOP transactions, the other main form of employee ownership, due to several factors. First, financing for ESOP conversions is tax-favored under U.S. law, making them attractive for investors seeking more traditional returns (more on that later) and less reliant on philanthropic capital for operational support. Second, there is more flexibility in ESOP transactions because a broader spectrum of outside capital can be used, including equity, and more providers can make it available than the CDFIs and specialty lenders that finance co-op conversions. Third, the size of businesses well suited for the different transactions are distinct: ESOP conversions are typically in the $3 million – $10 million range, while cooperative conversions are usually within the $300,000 – $1 million range.

Unlike worker cooperative conversions, ESOP conversions have not been associated with a social change or solidarity thesis. There are two imperatives to developing worker-centric ESOP conversions with a racial and economic justice angle. First is that many ESOP transactions have been executed as a profit-maximization strategy with little to no consideration of impact for workers, leading to negative outcomes for them. A readily available, proven worker-centric ESOP conversion strategy would provide a pathway for existing ESOP conversion funds to adopt an impact strategy. Second, and perhaps most important, is that if done well, a worker-centric ESOP approach may be able to expand the benefits and successes of the

movement for cooperative conversions into new areas of the economy. The ESOP model does not preclude workplace democracy, equity and wealthbuilding; in fact, there already exist ESOP companies that incorporate the cooperative principles, such as Sun Light and Power and Once Again Nut Butter.

To match these imperatives to the latent opportunity and demand for financing employee ownership conversions, Transform Finance recently released a report that outlines the viability of a novel financing model in a fund that combines a private equity buy-out with an ESOP structure. Such a fund would solve the selling owner’s pain points around a conversion, open up financing options beyond the provision of debt capital, and demonstrate a market-sustainable path for a wide range of capital to support mission-driven, worker-centered employee ownership.

The PE+ESOP Model

A traditional ESOP conversion in a succession context relies on seller financing, which requires the exiting business owner to extend a loan to the company for up to 10 years. This is usually not attractive for business owners, since it ties them financially to the business long after leaving. Scaling ESOP transactions requires a mechanism for outside financing rather than seller financing. Enter the PE + ESOP model.

The PE+ESOP model is a variation on the traditional private equity leveraged buyout, with the important difference that the ultimate ownership of the company’s equity rests in the workers through an ESOP trust.

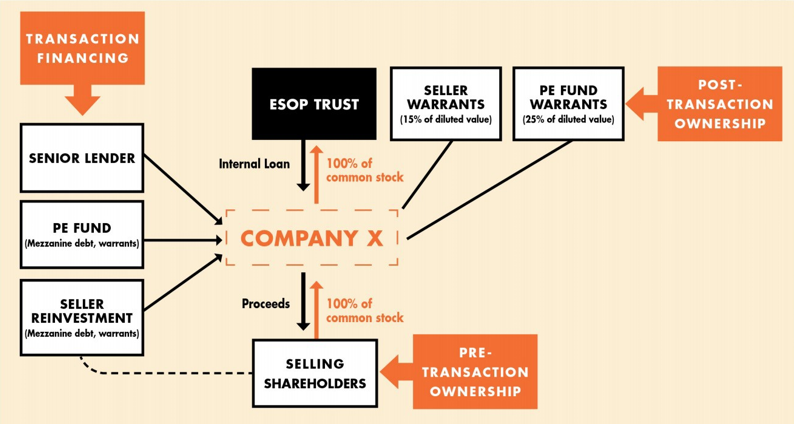

In a PE+ESOP transaction, the company itself buys 100 percent of its common stock, which is financed by the following three parties:

- A senior debt provider, like a bank, finances approximately 50 percent via a loan

- The PE fund provides approximately 30 percent of the transaction through mezzanine debt and warrants (essentially, contracts issued by the company itself that, similar to stock options, give the buyer the right to buy or sell the company’s shares at a set price on a certain date)

- The selling owners reinvest a portion of the sale proceeds back into the company, some approximately 20 percent of the overall transaction, also via mezzanine debt and warrants

The ESOP trust then takes a loan from the company in exchange for 100 percent of the common stock. As the company earns profits, a portion of the cash is allocated by the trust to paying off the loan from the company (and in turn, the company then pays off the external debt holders). As this loan is repaid, company shares held by the ESOP trust are allocated to the employees’ individual accounts.

The reinvesting seller (the initial owner of the company) and the PE fund now both have— besides a loan outstanding to the company—a right to buy shares of the company at a certain price. When they are ready to exercise that right and request the company to issue them shares, the company typically instead repurchases the warrants at the pre-established value. The company often finances the transaction by recapitalizing the mezzanine debt from the reinvesting seller and the PE fund with senior debt. The result is that all external parties are repaid, and the company stock rests fully with the workers through the ESOP trust.

There are currently at least four private equity groups that have used ESOPs in their transactions: Long Point Capital, Mosaic Capital Partners, Endeavour Capital and New State Capital Partners.

Ensuring sustainable impact

The favorable U.S. tax treatment of an ESOP conversion makes the PE+ESOP model attractive to both the private equity capital providers and the selling owners, who may be eligible to defer taxation on the capital gains from the transaction. This advantage can be a double-edged sword, however: traditional private equity is likely to maintain its laser focus on profit maximization even in the PE+ESOP context, rather than focusing on impact for workers and on the broader wealth gap. A non-impact minded conversion can result in overly high levels of debt imposed on the company, which would be placed on the new worker-owners. A profit maximization strategy also incentivizes paying down debt immediately rather than reinvesting profits into the company, squeezing workers’ job security, wages and stability.

For these reasons, PE+ESOP transactions must be designed and executed to avoid the extraction of the traditional PE model by adhering to impact parameters that protect the interests of workers.

This, in essence, brings the ESOP transaction rit of a worker cooperative conversion, particularly in the vein of those piloted by The Working World, which has an explicit mission of serving low-wage workers and people of color, and has pioneered the concept of non-extractive finance.

Through extensive consultation with employee ownership practitioners, we have created the following Impact Recommendations to mitigate most risks and maximize potential positive impact on the workers:

- Longterm, broad-based employee ownership Employee ownership

stakes must be available to all employees who meet basic eligibility requirements. Furthermore, the EO stake must be longterm—not temporary or a mere financing mechanism. This can be codified through adjustments to the company’s bylaws and trust documents, requiring the ESOP trustee to vote in accordance with oneperson-one-vote participant votes on key issues, such as the decision to dilute or dissolve the ESOP, or to sell the company.’ - Centering POC and low-wage workers

Countering the racial wealth gap via employee ownership transactions requires centering the voices of affected individuals and communities in the design of the transaction. This can be done in multiple ways: referral networks of entrepreneurs of color (as piloted by the Legacy Business Fund), geographic approaches (The Fund for Employee Ownership), and pipeline development in industries that have 1.) a significant workforce of low-wage workers and people of color and 2.) sufficient margins for building wealth for those workers. - Measured impact

PE+ESOP investors must develop and track a set of metrics to measure wealth building, employee social capital, tenure and mobility, benefits, demographics and other key impact areas. At the fund level, measuring such factors allows for evaluation on how to improve practices during the transition phase and in future deals. It also provides an opportunity for fund manager compensation to be tied to impact performance, rather than solely financial performance. At a field level, measuring impact provides valuable data for other potential fund managers waiting for demonstrated, viable pathways before executing similar transactions or modeling funds after early adopters. - Employee participation and power

Employee ownership investments should consider a democratic structure—in which workers nominate and elect the board of directors— for each transaction, and proactively build an ownership culture in its portfolio companies. This provides structural accountability of the management team to the workers, and results in longterm alignment of the management with a pro-worker mission. Developing such structures and culture includes creating culturally relevant, accessible tools for capacity building with workers. The timeline of the investment under the PE+ESOP model matches well with the period generally required for developing a culture of ownership vis-a-vis technical assistance. - Non-extractive deal structures

PE+ESOP funds must add more financial value for the affected stakeholders than what they take out as compensation for the investment. This notion was developed and popularized by The Working World. Specifically in deal structuring, non-extraction can take the form, for example, of establishing ceilings for investor returns that are commensurate with their risk, of not structuring collateral in ways that could leave the investee worse off in case of default, and in ensuring that the financial benefits to workers are not overshadowed by those to capital providers. In the context of the historical imbalance of power between workers and investors, additional protections in the case of PE+ESOP transactions aim to prevent 1.) over-leveraging the company’s assets in order to maximize payment to the selling owner through, for example, over-valuation of the company or the excessive use of warrants, 2.) reducing benefits or wages as a result of the transaction, and 3.) decertifying an existing union as part of the transaction, or otherwise creating profitability at the expense of ensuring quality jobs for the workers.

By using this model in a balanced way that does not solely focus on the extraction of financial returns, investors can play a meaningful role in preserving the millions of jobs that are at stake with the current wave of retiring business owners. Combining the spirit of the worker cooperative movement with the scale of larger conversions, ESOPs can provide stable, long-term employee ownership that prioritizes not just the wealth-building qualities of the ESOP trust but also democratic ownership and other features of quality jobs.

In light of concerns about private equity’s tendencies and the above impact recommendations, one can envision the ideal investor into a PE+ESOP fund as an impact-oriented asset owner, such as a foundation or family office, that is seeking to combine a primacy on impact with a reasonable expectation of return. Given that the returns are likely to be lower than traditional private equity, such investors could be attracted by a commensurate reduction in risk (for example, having a third entity, such as a municipality or another foundation, agree to assume part of the risk via a guarantee on the fund).

For new, untested funding mechanisms like the PE+ESOP model, it is particularly important to have an anchor investor who can jumpstart the fund and attract other investors through name recognition. One advantage of this approach is that the anchor investor can exercise outsized power in baking the impact recommendations into the fund. While labor pension funds are naturally aligned with worker interests, they are subject to significant limitations on the risk that they can take on novel fund models and first-time fund managers—they could, however, contribute significant capital once the strategy is proven.

There is an additional category of potential investors, beyond the ones approaching PE+ESOP from an pure impact angle: an investor may want to strengthen a supply chain connected to existing operations and see worker ownership as a way to do so, or prevent economic distress in a community because they would otherwise bear its cost in other forms (such as a municipality). They may also be pursuing a long-term investment strategy, which takes into account corporate consolidation and income inequality.

Our hope is that the PE+ESOP model outlined above can inspire and facilitate more conversions that reward the seller owners while also creating an authentic wealth-building opportunity for workers. Employee ownership advocates can play a role in facilitating conversions by understanding the variety of investment tools at their disposal— even ones that may at first blush seem foreign or that involve actors historically antithetical to worker well-being. We hope that the base model proposed is a valuable contribution for impact-oriented investors and the employee ownership field as a whole.

Andrea Armeni is a Co-Founder and Executive Director of Transform Finance. Armeni combines a corporate law and finance background with engagement in activism. He has taught at Yale Law, Université Paris Dauphine in France, and currently is an adjunct faculty member at the NYU Graduate School, where he lectures in the masters’ program. He serves as advisor to the United Nations’ Joint SDG [Sustainable Development Goals] Fund, and sits on the board of the NGO Finance for Good Brazil and of the investment fund CARE Enterprises, Inc. He recently authored “Innovative Financing Structures for Social Enterprises” and co-authored the briefing “Renewable Energy: Managing Investors’ Risks and Responsibilities.”

Curt Lyon is the Associate Director of Programs of Transform Finance. In this role, he helps steer the direction and vision of Transform Finance’s programs, manages major research and advisory projects, contributes to reports and briefings, and coordinates staff across program areas. In addition, he develops key language for narrative building around the intersection of finance and social justice and holds relationships with Transform Finance’s broad set of stakeholders. Before joining Transform Finance, Curt became inspired by the power of a more just and democratized economy when he worked with the New Economy Coalition and the Boston Ujima Project in 2016. He considers himself an active learner of community engagement with capital, multi-stakeholder governance structures, and scalable strategies that allow the disenfranchised to reshape and redefine power structures