Spring/Summer 2020

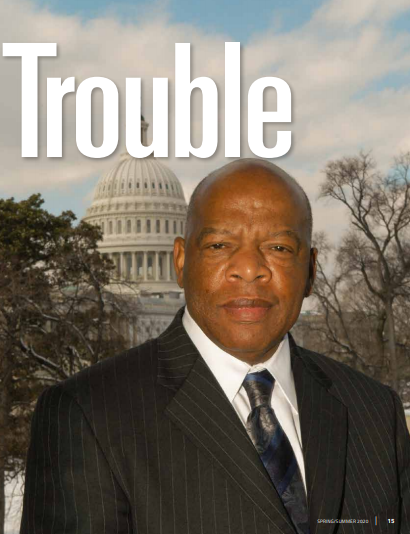

Good Trouble

A call to continue John Lewis’ cooperative legacy

By David Thompson

When civil rights icon and longtime public servant John Lewis passed away last month, he left a legacy that will forever inspire Americans to keep fighting for racial justice and equality— even when it means getting into what he called “good trouble.” Representative Lewis will be remembered for his exceptional life. Born the son of a sharecropper, he became a towering figure of the civil rights movement and a 17-term U.S. congressman representing Atlanta. As a young activist in 1965, Lewis was brutally attacked as he and other civil rights leaders marched across the Edmund Pettus Bridge from Selma, Alabama toward the state capitol of Montgomery in support of equal voting rights. Lewis bore the scars of a fractured skull from that march for his entire life—as does America.

Footage of “Bloody Sunday” stands out as one of the most oft-replayed instances of overt, violent racism in the U.S. At the time, it marked a turning point in the civil rights movement, shifting public opinion and galvanizing support for the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

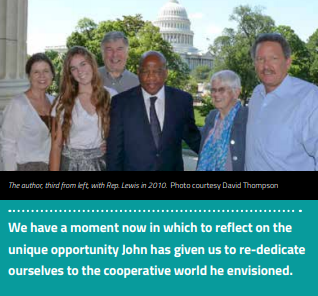

The last time I saw John Lewis was in May 2010. I was in Washington, DC being inducted into the Cooperative Hall of Fame. That afternoon, John told us the soul-stirring story of personally forgiving the white police officer who bludgeoned him on the Edmund Pettus Bridge. The officer was dying of cancer and wanted to apologize for his actions and be forgiven. John and the former officer had talked and then prayed together in the same room that we were in.

John Lewis will long be remembered for the person he was and the passions he held. Many will write of his character, his contribution to building a better America and his selfless willingness to push for and pursue change. He deserves every accolade and award he earned, for he represents the best of America. He saw the future of our nation and did all he could to lead us there. I will let others more capable than me lift up his lifetime of service.

What I want to focus on is John Lewis’ support for cooperatives. Throughout his years of public service, John always believed that cooperatives could build a better, fairer and more diverse and equitable America.

1958 – Highlander Folk School

At eighteen, John Lewis first learned about the power of cooperation while attending the Highlander Folk School in New Market, Tennessee, a social justice leadership training center that hosted Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King, Jr., among other Civil Rights giants.

In his autobiography, Walking With the Wind: A Memoir of the Movement, John wrote that before attending Highlander, he knew a lot about the uniquely interracial Highlander Folk School and its lonely, brave work striving for racial justice in the South led by its co-founders Myles Horton and Don West. At that time, Highlander itself was a cooperative and taught its attendees about the development and use of cooperatives.

It was at Highlander that John met Septima Clark, a 60-year-old organizer running a literacy and citizenship workshop called “The Progressive Club” out of the back of a food co-op on Johns Island, South Carolina. There, Clark worked with Esau Jenkins to teach Black people how to pass the rigid tests used to prevent them from obtaining the right to vote. This voter education was all done secretly in the backroom of a food co-op that Esau and other Black islanders had set up to meet their community’s needs. That effort went on to become the Citizenship School Program, whose 900 schools registered millions of Black people to vote in the South for the first time.

Rosa Parks attended Highlander in 1955 and was equally impacted by Septima Clark. As she later said, “I was 42 years old and it was one of the few times in my life up to that point when I did not feel any hostility from white people… I felt that I could express myself honestly without any repercussions or antagonistic attitudes from other people… It was hard to leave.” But she did, and only months later, with her newfound conviction, she refused to give up her seat on a Montgomery bus.

At Highlander, John heard Guy Carawan sing the re-worded hymn, “We Shall Overcome,” first written by Black composer Charles Tindley. It was also at Highlander that John told me he first sat down for a meal at the same table with white people. It would be a seminal moment. In his autobiography, John wrote, “Of course, I left Highlander on fire. That was the purpose of the place, to light fires, and to refuel those whose fires were already lit.”

1958 – Spelman College

Also in 1958, John attended a meeting at Spelman College in Atlanta on nonviolent resistance to segregation. There, John learned about the long history of pacifist resistance from Bayard Rustin. Rustin had already taught the same tactics to Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King, Jr. ahead of the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

At the same Spelman gathering, John met Ella Baker, who, by my account, is the most unsung woman of the American civil rights movement. In the 1930s, as National Director of the Young Negroes Cooperative League, Ella was developing cooperatives in Harlem and New York City. She taught a young civil rights activist Bob Moses about co-ops. She was then hired by the NAACP to teach about cooperatives throughout the country.

Ella also attended meetings organized by the Cooperative League of the USA (now the National Cooperative Business Association CLUSA International). She was the first staff member of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) to work for Martin Luther King, Jr. And she also became the first staff member of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), a group that emerged out of student-led sit-ins at segregated lunch counters across the south.

1963 – March on Washington

As newly elected chair of the SNCC, John was one of the “Big Six” who represented the organizers of the March on Washington. The other five members were: James Farmer, head of the Congress on Racial Equality and resident of Chatham Green Co-op in NYC, which had been sponsored by credit unions; Martin Luther King, Jr., a lifetime supporter of coops; A. Philip Randolph, a co-op writer who lived in the Dunbar Apartments, the first housing co-op for Black people in NYC; Roy Wilkins, Executive Director of the NAACP who later joined the Parkway Village Housing Co-op in NYC; and Whitney Young, President of the Urban League, which organized housing and other co-ops.

Bayard Rustin was appointed organizer of the March on Washington. At his co-op apartment in Penn South, Bayard hosted the first meeting of the group that would go on to lead the march. Rachelle Horowitz and Tom Kahn, who also lived at the same Penn South housing co-op, were key members of the group. Norm Hill, who also attended the first meeting and worked on the march, later moved to the co-op, and still lives there today.

Throughout 1963, Rachelle housed dozens of event volunteers at her Penn South Co-op apartment. Among them, in particular, were Eleanor Holmes Norton (today the non-voting Congresswoman representing Washington, DC) and civil rights activists Joyce and Dorie Ladner. In Walking With the Wind, John recounted being in NYC just before the march and having Joyce Ladner, Tom Kahn and Eleanor Holmes Norton read over his controversial speech. John’s speech would end up being the most contentious one of the day. Roy Wilkins wanted it removed from the program, but others threatened to boycott the event if it was left out.

Rachelle told me in an interview that the hotel in NYC where John was staying and practicing that speech had thin walls. The hotel manager asked John to practice his speech elsewhere or be evicted. So John asked Rachelle if he could practice at her apartment instead. Rachelle figured that the co-op’s thick brick walls would absorb the sound. But after hearing some particularly fervent renditions of the speech, Rachelle eventually kicked John out, too. A few days later, a 23-year-old John Lewis gave his speech to the nation from in front of the Lincoln Memorial.

A couple of nights before, Rachelle had also kicked Bob Dylan out of her apartment. Dylan had come over to practice the songs he was performing for the march. Dylan had an additional motive—to serenade Dorie Ladner for as long as Dorie would allow. He would sing song after song to Dorie until Rachelle told him it was late, and he needed to leave as the four women had work to do tomorrow. He left reluctantly but “The Woman in Jackson” in Dylan’s “Outlaw Blues” is assumed to be Dorie Ladner.

1967 – Southern Regional Council

In Walking With the Wind, John wrote about going to work for the Southern Regional Council (SRC) in Atlanta, Georgia, where he was made Director of the SRC’s Community Organization Project. John’s task was to establish cooperatives, credit unions and community development groups across the Deep South. “This was hands-on work, and I loved it. I felt at home again, literally,” he later wrote in his autobiography.

Also in 1967, John was one of the leaders who sponsored and supported the initial meeting of 22 cooperatives and credit unions that eventually led to the formation of the Federation of Southern Cooperatives/Land Assistance Fund.

1977 – Carter Administration

In 1977, President Jimmy Carter appointed John as the Associate Director of ACTION, the federal volunteer agency. John’s staff included 125 people in ten regional offices. The staff oversaw 5,000 Volunteers in Service to America (VISTA) volunteers and over 230,000 elderly volunteers. “We tried to help them through a range of programs similar to those I had directed with the Southern Regional Council,” John said. “We helped form cooperatives in rural communities.” In this role, John was also instrumental in providing a national contract to the Federation of Southern Cooperatives/Land Assistance Fund, which allowed the organization to sponsor more than 100 volunteers in a dozen southern states. This program helped the federation strengthen and support its membership region-wide.

1980 – National Consumer Cooperative Bank

I first met John in 1980, when the newly chartered National Consumer Cooperative Bank (NCCB) brought him on board as Community Relations Director to spread the word of cooperatives to Black leaders and communities. NCCB President Carol Greenwald asked me to arrange tours of Black communities in the U.S. where John could speak about the bank and its nonprofit arm as resources for cooperatives in Black communities. I had the honor of being on a two-week tour of California with John. Among those with whom we met were Los Angeles Mayor Tom Bradley, San Francisco Mayor Willie Brown, Assembly Member and now Congresswoman Maxine Waters, and State Senator Diane Watson. These Black leaders were all excited to see John and eagerly listened to the cooperative opportunities provided by the NCCB and its nonprofit arm. Later, Bradley and Brown both supported food co-ops assisted by the NCCB’s nonprofit arm.

1988 – Cooperatives in South Africa

In 1988, my wife Ann and I hosted Eldridge Mathebula, a South Africa activist whose organization, the Black Consumers Union, wanted to develop co-ops for Black people in South Africa. However, under apartheid only white people were allowed to develop and operate cooperatives. Eldridge’s organization invited me to South Africa to work with South African governmental agencies on a pathway to legalize co-ops for Black people. At the time, there was an international boycott of South Africa, which I did not want to violate. John, by that time, was a Congress Member representing Atlanta. In his office in Washington, DC, I laid out the pros and cons of going to South Africa and asked John for advice on whether I should go. In the end, John felt I certainly should. In his opinion, the opportunity was there to instigate Black cooperatives as democratically run organizations. In a nation that disallowed Blacks from voting and political power, cooperatives could be a nonviolent way to build a new society. In 1989, the Black Consumers’ Union registered the first Black cooperative in South Africa.

2017 – Federation of Southern Cooperatives/ Land Assistance Fund

2017 – Federation of Southern Cooperatives/ Land Assistance Fund

Throughout this life in public service, John was a good friend and champion of the Atlanta-based Federation of Southern Cooperatives/Land Assistance Fund. John spent decades working with the Federation to champion legislation to support Black farmers and combat discrimination at the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

In 2017, John spoke at the Federation’s 50th Anniversary in Birmingham, Alabama. During a stirring speech at the awards ceremony, John called cooperatives a “key strategy” in the Civil Rights Movement. Echoing Martin Luther King, Jr., he urged audience members to keep their “‘eyes on the prize’ of achieving true and lasting equality, despite setbacks.”

With John Lewis’ passing, we have surely lost a champion, but we honor a giant. The son of a sharecropper, John shaped the American conscience. We have a moment now in which to reflect on the unique opportunity John has given us to rededicate ourselves to the cooperative world that he envisioned. Now is the time for cooperators to return to getting into “good trouble.”

Cooperative historian David J. Thompson is author of Weavers of Dreams: Founders of the Modern Cooperative Movement and President of the Twin Pines Cooperative Foundation. David was inducted into the Cooperative Hall of Fame in 2010. He is currently writing a book on “Cooperatives Against Slavery and For Civil Rights.”