Fall 2022/Winter 2023 – Doorway to Dreams – Unlocking Opportunity Through Co-Ops

Building Community, Forging Respect

Home Care Co-ops Show a Better Way

By Sanjay Pinto

With the Covid-19 pandemic taking a particular toll on seniors and people with disabilities, home care workers have been a critical lifeline. Despite the risks of Covid-19 infection for themselves and their loved ones, they have provided crucial care support and helped to counter the acute social isolation many of their clients have experienced.

Recognized as “heroes” and lauded as “essential,” the conditions confronting home care workers have often revealed a basic hypocrisy beneath these accolades, however. In the early days of the pandemic, many lacked ready access to personal protective equipment. Fewer than half of states offered hazard pay for home care workers. In 2021, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, home health and personal care aides earned $14.15 an hour on average, which amounts to $29,430 at full-time hours—a status many struggle to achieve. It is hardly surprising, then, that the pandemic conditions have only worsened existing workforce shortages in the home care field. Why give so much to get so little?

In this context, worker co-ops can serve as an important tool to advance voice and dignity for home care workers, along with improvements in pay and other conditions. Given the larger forces at play, co-ops cannot win these struggles on their own. But they can play a significant role within broader strategies to make in-home care delivery better for workers and patients alike.

Swimming against the tide The low value accorded to home care labor is not an accident. Despite being foundational to basic life processes and all other economic activity, paid and unpaid care has long been devalued because it is overwhelmingly performed by women. Disproportionately led by women of color and immigrant women, the paid home care workforce is particularly devalued. Long after the end of slavery, most Black women engaged in paid labor were employed as domestic workers in many parts of the country, which often included providing various forms of in-home care support. In the New Deal Era, white Southern Democrats intent on preventing Black people from building collective power purposefully left domestic workers out of landmark labor and employment protections—exclusions that continue to wield impact today.

Starting in the 1960s, some home care services started to receive public funding support—part of a strategy to reduce the cost of long-term care (relative to care in institutional settings) and enable seniors to “age in place.” Often, employment within publicly funded systems creates a path to improved compensation. However, the demographics of the home care workforce have contributed to an assumption among policymakers that these services can be delivered on the cheap, contributing to low government reimbursement rates.

Starting in the 1960s, some home care services started to receive public funding support—part of a strategy to reduce the cost of long-term care (relative to care in institutional settings) and enable seniors to “age in place.” Often, employment within publicly funded systems creates a path to improved compensation. However, the demographics of the home care workforce have contributed to an assumption among policymakers that these services can be delivered on the cheap, contributing to low government reimbursement rates.

Given the fragmentation, invisibility and continued undervaluation of the industry, co-ops can provide an important set of channels for home care workers to connect with one another, claim a measure of control, and press for improved conditions. A 2020 report noted 14 active home care co-ops around the country employing more than 2,600 workers, with levels of pay that exceeded those of “non-cooperative industry peers.” With new home care co-ops having launched since that time, the sector is growing and building power in multiple ways. The larger forces that devalue home care labor must still be reckoned with, but there are ways in which co-ops can help take on those systemic challenges, too.

PROGRESS AND CHALLENGE

Cultivating community

Even while playing an outsized role providing undervalued paid care services for others, women of color and immigrant women often face acute challenges securing the care support they need in order to provide for their own families. In response to these conditions, they have often been leading innovators of mutualism and cooperation in providing care and meeting basic needs through community and extended kin networks. Many home care co-ops draw on these traditions of solidarity and mutual care.

Community Care Cooperative (CCC) was recently launched in Houston’s Third Ward, a mostly African American community with a rich history of activism and civic engagement. Rooted in a framework of Black liberation, CCC is made up of 13 Black women working as home care workers, community health workers (CHWs), or both. The co-op was formed following an assessment showing both that in-home care support was an important community need and that many women in the area had substantial experience working in the personal care field.

According to Assata Richards, a sociologist and co-op member who helped to spearhead its development, CCC seeks to counter the exploitative experiences that many of its members have had working in previous jobs. It also aims to provide a place of refuge given the racism many of its members continue to encounter in other domains. In the face of past and present traumas, CCC is building a space of solidarity. For example, while CHWs generally earn more on average than home care workers, members who log hours as CHWs are donating part of their pay to increase the earnings of their home care colleagues.

Founded a decade ago in Brooklyn, Golden Steps is a home care worker co-op comprising new immigrant women from Central and South America. Many have experienced labor violations and acute precarity working in the informal economy. In addition to rigorous job-related training, Golden Steps provides extensive training and education on labor rights and strategies for communicating effectively with clients, and offers a community of support for talking through challenges that arise. The co-op has also committed itself to providing the best possible care for a diverse clientele with different needs. Members receive training in cultural competency and providing support to LGBTQ+ clients with sensitivity and care.

Building and maintaining democratic community is not easy. Conflicts arise and members must negotiate multiple demands on their time. The recent growth and development of large-scale co-ops in home care and other adjacent fields also intensifies questions of internal equity and representation. Absent institutionalized commitments to act otherwise, executive leaders and co-op developers at a level removed from the front lines may operate from a charity mindset and unconsciously accept racially tinged notions about the capabilities of the workforce, undermining grassroots democratic control and reproducing toxic dynamics embedded in the broader culture. Amid important opportunities to build home care and other care worker co-ops at greater scale, addressing these concerns head-on is critical.

Advancing mobility

In addition to the benefits of a supportive community, many home care co-op members can earn higher pay than they would doing comparable work elsewhere. Golden Steps members identify several factors that, in their view, contribute to higher pay. In an environment where many would otherwise be working independently, working for the co-op commands a certain amount of recognition and respect. The rigorous training the co-op provides also confers legitimacy and helps members to provide the high-quality services for which it is known. When compared to other agencies, the administrative overhead is lower at Golden Steps, allowing workers to keep a larger cut of what they earn.

Of course, pay and other conditions are also rooted in a landscape that extends far beyond the boundaries of any individual enterprise. For this reason, several co-ops of domestic workers in the informal, private-pay economy have become engaged in larger organizing efforts to change norms and attitudes at a neighborhood and community level and strengthen the legal obligations of employers at a city and state level.

Home care co-ops in the publicly funded system operate in a more clearly defined institutional environment and can tap into large referral networks in ways that support building at scale. Founded in 1985, Bronx-based Cooperative Home Care Associates (CHCA) is the largest fully functioning worker co-op in the country, with a workforce of nearly 2,000 that provides services mostly within the publicly funded system. Workers have access to peer mentoring and direct lines of communication to the co-op’s leadership team— factors that may help explain the co-op’s lower-than-average turnover. But CHCA’s Vice President for Human Resources, Denise Hernandez, notes that low government reimbursement rates continue to constrain pay.

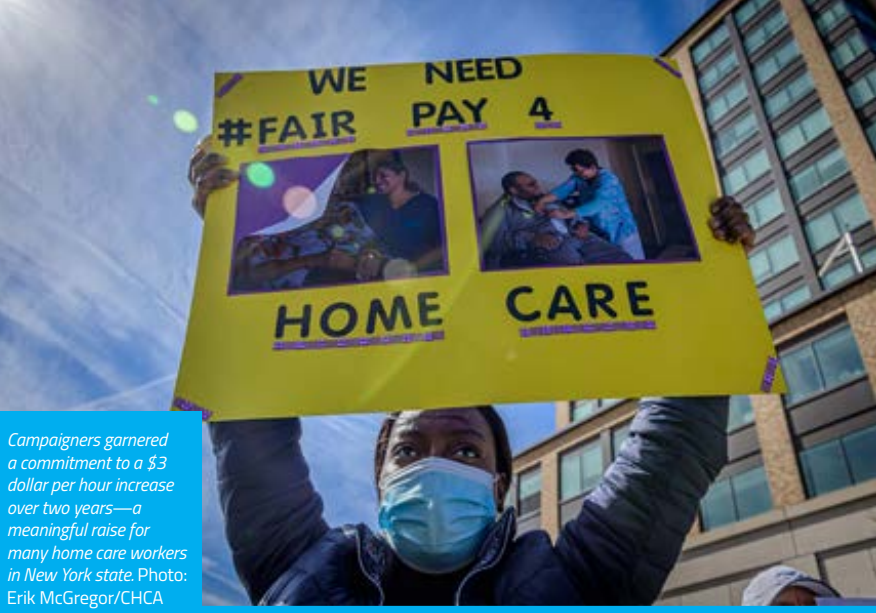

Recently, CHCA took a leading role in a “Fair Pay for Home Care” campaign in New York state, working alongside a coalition of allies including 1199SEIU, the union representing its members. Kim Alleyne, a long-time CHCA member, was among those playing a central role in the campaign, which included sharing her perspective on the difference a pay increase would make in meetings within elected leaders. Though disappointed not to win the full increase they were seeking, campaigners did garner a commitment to a $3 dollar per hour increase over two years—a meaningful raise for many home care workers in the state.

Co-ops can also help to provide a basis for occupational mobility. According to Hernandez, more administrative staff are former home care workers than other comparable agencies. At Community Care Cooperative, cross-training enables several members to work both as home care workers and CHWs. This flexibility permits people to work more hours, and it also provides a path for home care workers to gradually move into more lucrative CHW roles—a title that could see increased demand through new federal funding commitments.

For Zenayda Bonilla, who immigrated to the U.S. from El Salvador in 2003, joining Golden Steps created a new sense of possibility. Having cared for her father while he was ill with terminal cancer, caregiving evoked pain. In Golden Steps, however, she found a nurturing community that helped her to embrace the skill she brought to the role. The co-op’s training regimen also provided a sense of professional identity that eventually enabled Bonilla to envision and pursue an evolution in her journey as a care provider. Today, she is studying to be a social worker even as she helps Golden Steps navigate a challenging phase exacerbated by the stresses and strains of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Building Wealth

Through shared ownership, building wealth is a well-documented potential benefit of co-op membership. Many home care co-ops in the U.S. are not structured in a way that directly generates wealth for members through shared ownership. However, higher pay rates at co-ops like Golden Steps can make it easier for workers to build up savings or avoid going into debt. At CHCA, those who elect to become members do become shareholders, which entitles them to dividend payments in some years. All CHCA workers who pass the probationary period are also eligible for healthcare and other benefits that bolster their economic security.

The potential for cooperatives to build wealth and long-term economic security extends beyond the world of work. After several years in development, Heartsong Caregiver Cooperative recently launched in Washington State, which is home to several home care worker co-ops. The co-op has 14 members from a variety of backgrounds working in the private pay segment of the market. According to Kathie Rivas, Heartsong’s Administrator, she and five other coop members live in Whispering Pines, a 55-home mobile park that became a resident-owned co-op community in 2013. The development provides residents with secure and relatively low-cost housing. It has also proved to be fertile ground for recruiting new members into Heartsong, creating a multifaceted network of mutualism and cooperation.

As Richards from the Community Care Cooperative points out, co-ops can increase “wealth” in a variety of ways that include not just building up economic assets but augmenting social capital and enhancing self-efficacy. These modes of wealth building have both a collective and an individual dimension. And Bonilla’s trajectory shows how the two are interlinked in ways that can spill over to the benefit of surrounding communities. During the pandemic, she helped 50 others apply for financial support from New York State’s Excluded Workers Fund— an accomplishment noted when she was named “Cooperator of the Year” by the U.S. Federation of Worker Cooperatives in September 2022.

Significant wealth is generated through what co-op members build among themselves. But an important question for the future is how co-ops providing home care and other essential services can be better supported to build and grow in ways that advance equity and inclusion at scale for multiple stakeholders.

THE ROUTE AHEAD

With demand for home care set to continue its rapid growth, worker co-ops can help to empower home care workers, support their ability to build economic security, and provide a foundation for the delivery of high-quality care. Below are some key action areas that could help to advance the development of home care worker co-ops as part of a larger systems change strategy for the industry. Across these areas, explicitly centering equity and inclusion is critical to ensuring that coop development presses in the direction of social inclusion, racial and gender equity, and economic justice.

Training and education Building accessible and sustainable training infrastructure could provide a foundation for creating home care co-ops at greater scale. As Richards suggests, this training should be trauma informed, accounting for the multiple ways in which experiences of racism and sexism inform the building of cooperative connections among frontline care workers. Meaningful, measurable commitments to anti-racism at an individual and organizational level are also essential for all of those within the ecosystem.

Development financing As Minsun Ji highlights in her piece in this issue of the Cooperative Business Journal, there are numerous private sources of capital that can help to support co-op development in historically marginalized communities. Public funding that preferences minority and women-owned businesses could also provide support. And, to help embed home care co-op development within public delivery systems, public funding for long-term care could be routed to support co-ops and other high-road models that benefit different stakeholders.

Cooperation among cooperatives Many home care workers experience the impact of structural racism and other related inequalities along multiple fronts. They also frequently have experience with a variety of different forms of cooperation and mutualism. The example of several Heartsong Home Care Cooperative members being members of the Whispering Pines Cooperative residential community illustrates the potential for weaving together different co-op sectors in ways that deepen community and advance economic security.

Cross-movement connections The growing interest of unions in supporting co-op development within the healthcare system and other sectors could help to build the cooperative economy at greater scale while connecting deep workplace democracy with broader structural power. In addition to supporting co-op startups and conversions, unions and other movement allies could help to support co-ops by mobilizing the buying power of their members and constituencies, as well as collaborating with co-op leaders on supportive policy and legislation.

Policy advocacy As CHCA’s role in the Fair Pay for Home Care Campaign demonstrates, co-ops can help to elevate the voices of frontline workers within policy debates around investments that directly affect pay and other conditions. Of course, a variety of policies at different levels of government can also support co-op development—for example, in addition to support for training and direct funding support for the creation of co-ops, giving workers a “right of first refusal” in cases where existing owners plan to exit could help facilitate conversions to worker ownership.

Changing the narrative Even as the Covid-19 pandemic and recent movements challenging structural racism and sexism highlight deep inequities across the care sector and other social arenas, business as usual largely prevails. Highlighting stories such as those sketched above can demonstrate the leadership and ingenuity of those facing steep odds in forging a better way. It can also help to foster wider commitments to supporting models that deepen democracy, raise standards, and address critical community needs.

Sanjay Pinto, PhD, is a Brooklyn-based sociologist. His research focuses on strategies for building worker power together with racial and gender equity. With Camille Kerr, he co-directs the Program on Unions and Worker Ownership at the Rutgers School of Management and Labor Relations.