Fall 2019 – The Next Economy

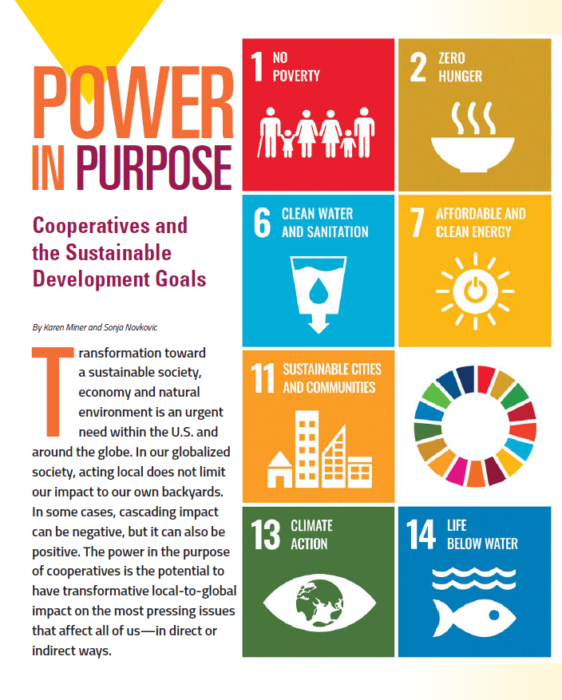

Power in Purpose

Cooperatives and the Sustainable Development Goals

By Karen Miner and Sonja Novkovic

Transformation toward a sustainable society, economy and natural environment is an urgent need within the U.S. and around the globe. In our globalized society, acting local does not limit our impact to our own backyards. In some cases, cascading impact can be negative, but it can also be positive. The power in the purpose of cooperatives is the potential to have transformative local-to-global impact on the most pressing issues that affect all of us — in direct or indirect ways.

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) require changes to business as usual, and while they are an excellent fit with the cooperative business model, existing cooperatives have not transformed sufficiently to meet these calls to action. If all corners of the cooperative sector were to use the SDG framework as a call to action, there is deep potential to create meaningful impact. Failing to show leadership in this area is a missed opportunity that will ultimately contribute to the continued degradation to social, economic and environmental systems within our communities.

The development process for the SDGs was initiated at the UN Conference on Sustainable Development (Rio+20) in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil in 2012.1 “Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development” was adopted in 2015 through a resolution at the UN General Assembly in New York.2 This 2030 Agenda established the 17 SDGs and related 169 targets. The aim of the SDGs is to address the most pressing contemporary issues of economic, social and environmental development — poverty, hunger, health, education, jobs, inequality and climate change, among others.

While the previous Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and the SDGs both contain specific objectives, targets and indicators to track progress, the SDGs are more ambitious and include developing and developed countries in both the process of consultation and targets. It is a global effort to address global issues through partnerships and transformative action. The 17 interconnected goals address systemic issues facing the planet.3 Five fields (called the “5 P’s”) of critical importance recognized by the signatories of the SDGs are People, Planet, Prosperity, Peace and Partnerships.

The consensus is that all stakeholders — governments, private sector and civil society organizations — need to contribute equally to the SDGs.4 While businesses are recognized to be the source of economic growth, employment and innovation, they are often at the root of environmental degradation and social inequity when they are driven purely by profit. Critics therefore debate whether businesses can truly contribute to the transformation of the global economy and society unless they first transform their business5 and deploy a different economic paradigm to replace neoliberal systems and policies.6 To that end, this paper offers a discussion about contribution toward SDGs by cooperatives as a distinct business form with dual socio-economic purpose.

Transformative change

Sustainable Development Goal stakeholders acknowledge that marginal policy changes will not be enough for meaningful global impact; rather, what is needed to reach the targets are transformative long term changes.7 The UN’s efforts to deploy new approaches to development — in particular to engage the potential agents of transformative change — include the promotion and scaling up of the Social and Solidarity Economy (SSE).

“The forms of economic activity that make up the SSE generally acknowledge and apply a set of principles, norms and practices that seem particularly conducive to meeting peoples’ basic needs and promoting environmental protection, decent work, the equitable distribution of resources and profits, and democratic forms of governance. Such attributes stand in sharp contrast to ‘business as usual,’” the UN’s Peter Utting wrote in “Mainstreaming Social and Solidarity Economy: Opportunities and Risks for Policy Change.”

Cooperative enterprises form the core of the social economy.8 Although all types of cooperatives are included in the SSE concept, we argue elsewhere9 that all cooperatives are not made equal: some (Type 1) are created to serve as agents for social and economic transformation and pursue explicit social, economic and/or environmental objectives; while others (Type 2) are motivated purely by increasing economic value to their members. For those in the latter category, a paradigm shift is needed to embrace the full potential of the cooperative business model and contribute to the pressing issues of our time.

All cooperatives are associations of members; as such, they fall under the umbrella of democratically governed and member-owned and -controlled enterprises.10 Utting’s assertion — that the SSE is about “reasserting social control over the economy by giving primacy to social and often environmental objectives above profits, emphasizing the place of ethics in economic activity and rethinking economic practice in terms of democratic self-management and active citizenship” — applies to all cooperatives that abide by the International Cooperative Alliance’s Statement of Cooperative Identity.

Cooperatives have the potential to instigate transformative change as they rest on a different (not-for-profit and people-centered) logic. Anchored in local communities, they operationalize ethical values such as self-help, equity and solidarity. They address the structural causes of inequality and social injustice, which are the root causes of contemporary development issues, rather than just treat the symptoms. However, like the SSE more generally, cooperatives are exposed to institutional barriers and isomorphism (the tendency of institutions that face similar conditions to develop similar processes or structures),11 thus curbing their full potential for social transformation.

Isomorphic tendencies are more pronounced in larger, more mature cooperatives, especially as the conditions for their initial need are no longer a driving force — e.g. those of socio-economic injustice or market failures. For example, cooperatives that formed as a response to a lack of access to goods or services may find themselves in competition with other types of enterprises years after their establishment.12 In order to serve their members in these new market conditions, cooperatives need to stay in touch with member and community needs and find purpose in protecting member vulnerabilities. Deep forms of member participation, engagement and social innovation are key elements of success in these efforts.

The SDG framework, targets and indicators can serve as a tool to reinvigorate the difference cooperatives make in their communities. Cooperatives not only contribute to SDGs, but also serve as a vehicle to achieve many of the goals. Historical examples abound: from the war-ravaged Emilia Romagna region in Italy that is currently one of the most developed regions in Europe to the Kerala state in India, Kumasi region in Ghana, Mondragon region in Spain, and Parana state in Brazil. With human dignity as their driving force, cooperatives have provided well-paying jobs, reduced income inequality, lifted people out of poverty, secured access to finance and energy sources, and provided healthcare and education. Access to cooperative finance is a critical element in the ability of cooperative networks to contribute to the sustainable development of entire regions. The role of credit unions should therefore not be understated.

It is easy to become overwhelmed by the magnitude of the Sustainable Development Goals. Efforts have been made, specific to cooperatives, to shed light on some of the areas where cooperatives can focus their impact. For example, the International Cooperative Alliance (ICA) launched Co-ops for 2030 in July 2016. Using the SDGs as a basis, the Co-ops for 2030 campaign determined four action areas viewed as most relevant to the cooperative model: eradicating poverty, improving access to basic goods and services, protecting the environment, and building a more sustainable food system. For cooperatives in the food and agricultural sector, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) provides even more guidance.

This narrowing of focus into four key areas can give the impression that these are the only areas of work for cooperatives, but this list is not exhaustive: one can always revisit the 17 SDGs to determine other priority areas. It is not difficult to develop frameworks to guide specific sectors. As an example, a credit union leadership program has done just that.13

Credit unions as agents of community development

Credit unions are income-pooling institutions. Under isomorphic pressures in mature financial markets, they are often perceived to be financial service providers like any other. Their historical role has been to pool community income, pool risks and invest in the real economy, therefore serving as vehicles for community development. As cooperatives, credit unions can play an important role in localizing the SDG implementation. However, we are seeing intense regulatory and competitive pressures on credit unions. These isomorphic pressures lead to weaker credit unions that may underperform in the delivery of community, economic and environmental impact.

To linger on the credit union model, the SDGs are a lens through which impact can be understood, implemented and measured. SDGs are specific issues that bring to light unmet needs and illustrate how impact is created and measured.

To illustrate this point, we draw attention to the Credit Union Development Education (DE) Program that has been running in the U.S. since 1982.14 This program is also active in Canada, the Caribbean, Africa, Europe and Asia. The program’s purpose and curriculum is framed by “development issues” language, and each arm is focused on the needs for development in the host countries or regions.

The Canadian version of the program (CanadaDE) is hosted at Saint Mary’s University and attracts an international audience typically comprised of staff and participants from the U.S., Canada, the Caribbean and Africa. The program curriculum starts with a foundation built on the cooperative enterprise model with an overlay of the SDGs. The use of the SDGs caters to credit unions, illustrating the fit across four pillars — equitable access; economic empowerment; healthy environment, strong communities; and participation and inclusion. When studied, one is hard pressed to identify an SDG for which the cooperative model is not a good fit, and the use of these four pillars (while different from the ICA action areas) resonates with cooperative financial institutions. Furthermore, while some may be given greater focus, none of the SDGs are excluded in the DE program.

Use of the SDGs links easily to tangible, operational examples. For example, in credit unions, financial literacy is an imperative to manage a credit union’s risk profile but also to counter low levels of financial literacy, high personal debt and bankruptcy. This has a direct link to SDG 4 (quality education) as well as SDG 8 (decent work and economic growth). Indirect links to other SDGs can be identified, as financial security has cascading benefits tied to poverty, hunger, health and well-being.

While the DE leadership program was designed for delivery to the credit union sector, the content fits all cooperative sectors. The program’s purpose of achieving a just and equitable social, economic and environmental systems is the model that we must all be working within to maximize the development potential of cooperative enterprise.

The following examples illustrate this deep connection between the cooperative purpose and the SDGs that the DE program unpacks.

Cooperation among cooperatives

Like all other cooperatives, credit unions subscribe to the 7 Cooperative Principles, including Principle #6, “Cooperation Among Cooperatives,” but these alliances do not come naturally to all credit unions. One notable example of a cooperative initiated by a credit union is the Growing Our Future Childcare Co-operative in Newfoundland, Canada.15 This cooperative’s creation story is the direct result of deliberate changes within Leading Edge Credit Union over the past five years. Under the CEO’s leadership, the credit union has shifted toward a values-based financial cooperative.16 This transformation was initiated and continues to be fueled by a belief in the power of cooperative education (Principle #5) and deep implementation of that education at all levels of the organization.

Prior to the launch of the childcare co-op, Leading Edge Credit Union was the only cooperative in town. This new cooperative now provides daycare services to 40 families (including low-income families) and employs 11 people. When compared to the SDGs, impacts can be demonstrated clearly across six goal areas: no poverty, good health and well-being, quality education, decent work and economic growth, sustainable cities and communities, and gender equality. In rural communities like Newfoundland, the benefits of a new daycare cannot be overstated. Growing Our Future Childcare Co-operative is building community cohesion, supporting future generations, and fueling the region’s economic development.

Impact in purpose

Established in 2009, the Global Alliance for Banking on Values (GABV) is a network of values-based banks committed to “using finance to deliver sustainable economic, social and environmental development.”17 With such a focus, the work of this network is closely aligned with the SDG framework and cooperative financial institutions. In the U.S., four of the nine members are cooperatives: Missoula Federal Credit Union, National Cooperative Bank, Verity Credit Union and Vermont State Employees Credit Union.18 The triple bottom line (people, planet and profits) and real economy focus of the GABV makes its framework a strong proxy for the SDGs.

Vancity Credit Union — a Canadian member of the GABV — makes the connection between impact and the SDGs explicit in their annual report. This approach is a quantitative illustration of impact. “Vancity’s values-based banking model is aligned with the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals to end poverty, protect the planet and ensure prosperity for all by 2030,” their 2018 Annual Report states. Based on methodology developed by the Global Alliance for Banking on Values, the accompanying table shows how the credit union’s assets support each of those goals.

Furthermore, Vancity has determined that their work aligns most closely to seven of the SDGs. Not all of the impact is about the asset base of the credit union. Instead, it also points to the fundamental people-centered aspect of the cooperative enterprise model through such examples as commitments to living wage, diversity and inclusion.

Closer to Washington, DC, Carla Decker, president and CEO of DC Credit Union, is also a champion of the SDGs. In part, this is a result of her longstanding involvement in the DE programs in the U.S., the Caribbean and Canada.

“Our mission of financial inclusion may not be self-attributed as an effort to further the SDGs, but you will see the direct impacts,” Decker said — especially in goals #1 No Poverty, #5 Decent Work & Economic Growth, #10 Reduced Inequalities, #11 Sustainable Cities and Communities, and #17 Partnerships. Contributions are also being made to #4 Quality Education, #12 Responsible Consumption and Production, and #16 Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions.

Decker’s responses on SDG contributions are a result of a deep connection with the cooperative business model. A case study on DC Credit Union written by Margaret Lund as part of the ABCs of Cooperative Impact project19 and immediately following this article, is a testament to the deep alignment both within that project’s areas of impact, but also cooperative values and principles. Therefore, linking that impact to the SDGs is a natural extension. DC Credit Union illustrates the importance of going deep and being authentic in all aspects of how a cooperative is governed and managed over the long-term.

Power in purpose

Cooperatives are self-help organizations that address their members’ needs, making them a natural vehicle for sustainable development. They address market access, scale up production, provide decent jobs, create community-owned renewable energy and more — in part due to their democratic governance. It is imperative that cooperatives stay in touch with their members’ changing needs. They must also address external conditions such as climate change, demographic shifts and migration. The UN Sustainable Development Goals are a powerful tool cooperatives can use to demonstrate their power in purpose.

Sonja Novkovic is a Professor of Economics and Academic Director of the International Centre for Co-operative Management at Saint Mary’s University in Halifax, Canada. She is a member of NCBA CLUSA’s Council of Cooperative Economists and a regular contributor to the Cooperative Business Journal.

Karen Miner is the Managing Director of the International Centre for Co-operative Management, where she works with cooperative and credit union professionals from around the world.