Fall 2019 – The Next Economy

A Path to Shared Prosperity

Insights from ESOPs reveal the potential of employee ownership

By Janet Boguslaw and Lisa Schur

With growing wealth inequality in the U.S. and an increasingly fragmented relationship to the workplace driven by contingent and contract work, it is critically important for individuals, families and communities that the rewards of work take center stage.

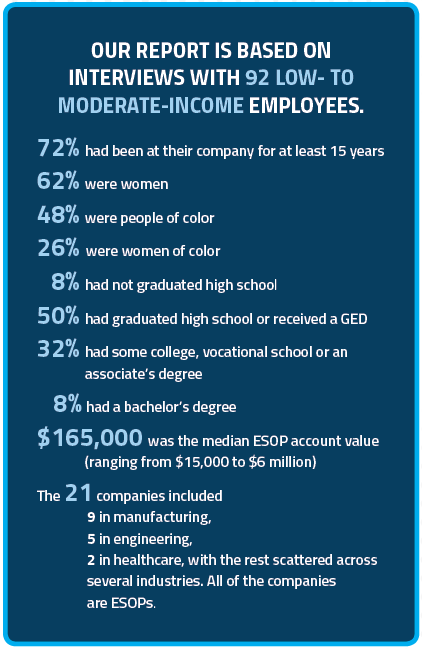

In 2015, the W.K. Kellogg Foundation engaged the Institute for the Study of Employee Ownership and Profit Sharing at the Rutgers University School of Management and Labor Relations to conduct a qualitative study examining the potential impacts of employee ownership for low- and moderate-income employees and their families. Its purpose was to provide insight into the role of employee ownership in supporting employees’ asset/wealth accumulation and related issues of financial security, economic mobility, and family well-being. With a large research team, we conducted interviews with long-tenured employees having low- to moderate-incomes at companies with Employee Stock Ownership Plans (ESOPs).

ESOPs and worker cooperatives are similar in that both involve broad-based ownership of a firm by its workers. One difference is that in a cooperative, company decisions and board elections are conducted on a one-person/one-vote basis, while in the typical ESOP workers do not elect the board and major decisions are conducted on a one-share/one-vote basis (although ESOPs can be set up to give one vote to each employee). Another difference is that funding for cooperatives typically comes from cooperative member savings, while funding for ESOPs is often borrowed from lenders, with the ESOP trust promising to repay the loan out of future earnings. The cooperative model is most frequently used to start new businesses, while ESOPs are generally used to buy out existing businesses (often from retiring owners). Given that both models involve broad-based ownership, and some ESOPs try to involve workers in decisions in order to create a greater sense of ownership, important lessons from our study of ESOPs have the potential to inform worker cooperatives.

Our study1 focused on interviewing women and people of color. In this article, we want to highlight three of our findings on the relationship of employee ownership to

- shared prosperity and wealth accumulation across race and gender categories,

- intergenerational transfers of wealth and wellbeing, and

- cooperation, participation and skill building.

The role of assets and ownership

Why is asset building important? The reality and lived experience of expanding wealth inequality in the U.S. is well documented. Today, the top 10 percent of households own more wealth than the bottom 90 percent combined. Assets are an alternative term for wealth or the collective set of resources held, in both tangible and intangible forms, which can be leveraged or invested for economic stability, security and wellbeing. Wealth is not built through income alone. It is the product of equity built through home ownership. It is cash savings from earnings, profit sharing, gifts or inheritances, and holdings of stocks and bonds. It is ownership of vehicles, retirement accounts and businesses. It is education, job skills and experience, and access to opportunity. It is the product of good health and healthcare, social networks and support, and more. Since wealth consists of more than simply cash, income or stocks, we refer to all of these components of wealth as assets. The combination of resources that constitute a household’s assets enable individuals and families to move from just making ends meet to managing life’s challenges and being able to plan and invest in the future.

Shared prosperity and wealth accumulation across race and gender categories

We compared the wealth of the individual workers in our sample to the wealth of single workers in national samples. This is an appropriate comparison because the data from our study are about individual workers’ 401(k) and ESOP accounts, thus we compare individual workers (our sample) with individual workers (national sample) in the same income categories. The individual earners we studied have much more total wealth through their ESOP and 401(k) accounts than single male and single female workers’ total wealth nationally. The comparisons are especially striking for workers of color, who generally tend to have lower wealth levels across the U.S. For instance, black women in our study had an average of over 275 times the wealth of black single women nationally. Still, in our study sample of ESOPs, black women have about one-fourth the average wealth of black men, white women and Latinx employees. All of these groups of employees have lower assets than do white men in our low- to moderate-income sample when considering both ESOP and 401(k) accounts, although they have higher average assets than single white men in the national sample. Employee ownership does not eliminate racial or gender wealth gaps, since ownership stakes are typically based on income that reflects racial and gender disparities. However, when compared to workers at traditional firms, women and people of color in employee-owned firms have significantly more assets.

As shared capital organizations, cooperatives and ESOPs can learn a lot from each other and, together, can fight wealth inequality.

A crucial point is that employee ownership wealth does not substitute for lower wages or other forms of wealth. The most recent research on this issue comes from Nancy Wiefek at the National Center for Employee Ownership’s study of the U.S. National Longitudinal Survey. This work provides evidence that young ESOP workers have 92 percent higher median wealth than their non-ESOP working peers. Importantly, it finds the ratio of household income to poverty levels is higher for young ESOP workers both overall and among single women, single women of color, workers with children age eight or under, and those with less than $25,000 in wages. Young ESOP workers also tend to have separate additional diversified 401(k) retirement plans. And, the median wage income of low-income women (earning less than $30,000) in employee owned companies was $21,000 compared to $17,000 among low-income women who were not employee owners.

Intergenerational transfers of wealth and well-being

ESOPs offer the opportunity for making intergenerational investments, creating opportunities for parents to help their children while still living, as well as potentially through the inheritance of ESOP values after death. They are also a form of life insurance, as a few workers we interviewed noted. If they should die before they retire, the ESOP value will be transferred to their families. Several mentioned the sense of security this provided them. ESOP accounts can also be drawn upon to reduce debt or cover unexpected economic shocks, as they represent resources that are not income dependent. Among employees who reached the age or years of tenure at the firm when they became eligible to either borrow or draw upon their ESOP accounts, a number say this enabled them to spend on their families while still retaining resources for retirement security. They used ESOP accounts to pay for children’s college tuition, weddings and down payments on homes. Others say that they are planning, once retired, to use the ESOP for these purposes. Many report that they will be secure in retirement and will not have to draw on their children’s resources for security and well-being. Several of the interviewees talk about their hope that they will have some resources to pass on to their children or grandchildren when they die. Parental ESOP wealth transfers to children while living increase young and adult children’s security, investments and next-generation opportunities.

Cooperation, participation and skill building

Employee ownership can help foster positive workplace relations and build employee skills. A study that reviewed results from 102 samples with over 56,000 firms found that there is a small but strongly significant link between employee ownership and better economic performance on average.2 The interviews provided a number of examples of how the ESOPs can create an ownership culture that encourages cooperation among employees. One woman said, “Things changed when the company became employee-owned. There is more of a sense of community,” while another said she feels “more secure at an employee-owned company… There is less conflict between employees… Management and co-workers care about me, not just as an employee, but as a person.”

Several employees gave specific examples of how the ESOP changed their views and behavior, such as a woman who said she told other workers not to be “so quick to FedEx everything” and another who said that people are more careful with company money “because it’s our ESOP dollars.”

National survey data show that employee owners are more likely than other workers to receive company-sponsored training — close to two-thirds (66 percent) of employee owners received company training in the past year compared to less than half (46 percent) of non-employee-owners, based on analysis of the 2014 and 2018 General Social Surveys. While ESOP companies vary, many of them provide opportunities for participation and training, such as financial education for understanding the ESOP model and company finances along with open book management.

One good example is a company that integrates work structure with workforce development. In this company, employee-owners at all levels are included in training and education programs for career advancement. Attendance at ESOP conferences is rotated to give everyone an opportunity to learn from them, and all employees are included in the annual business planning cycle when plants are shut down for a few days so that employees can help develop priorities and operational plans for the coming year. “I started here as a very shy person,” one employee said. But participation in leadership training, running meetings, attendance at ESOP conferences and the opportunity to be heard have given her the confidence to voice her views and lead others — skills she says are useful in her professional and personal life.

One worker put that spillover effect this way: “What I learned [at work] made it easier for me [to navigate daily life] — I felt more comfortable talking to my kids’ teachers, coaching my kids’ baseball team, dealing with the other parents, and just being more comfortable in my neighborhood.”

Translating findings into action

We learned a lot about strategies ESOPs can use to build assets for their low- to moderate-income workforce. While there is much more still to learn, we can begin to provide some direction. Our report details a number of key insights and possible suggestions about how to enhance the asset building opportunities from ESOPs from the point of view of different stakeholders. Several strategies can be particularly effective in building the assets of the low- to moderate-income workforce. These include the following:

- Provide financial literacy training and make linkages to personal family budgets This helps inform employees about the ESOP business model while helping transfer their new financial skills and knowledge to other contexts that may bolster personal asset development.

- Provide tuition support for both degree and non-degree courses Pay for tuition upfront and provide mentoring and support for success within the workplace. Engage more senior staff to coach or tutor employees for up to 2-3 hours per week in subject areas on company time. When needed, allow flexible scheduling so employees can take classes or prepare for exams. This saves personal budget assets and builds human capital.

- Adopt a more progressive ESOP share structure that ensures the lowest-paid employees receive a larger percentage of income share of ESOP value each year, consistent with pension law. This is one way to overcome some of the wealth inequality gap that continues even within ESOPs when share value is tied to income or earnings.

Public policy can also play an important role in advancing asset building through ESOPs. A variety of federal, state and local policies are designed to encourage employee ownership. Two of these are:

- The Main Street Employee Ownership Act of 2018 directs the Small Business Administration to support employee ownership in a variety of ways including loans, loan guarantees and technical assistance. This can help expand the opportunities for employee ownership conversions that will benefit low- and moderate-income earners. It could also be used to provide workforce education and training for ownership.

- The Preferred Status Certification would allow women-owned, veteran-owned and minority-owned ESOPs to retain their preferred status certification because they are majority owned by an ESOP trust. Instead of viewing the trust as a legal entity and disqualifying an ESOP-owned company, certifying agencies could instead consider the identities of the ESOP participants in whose interest the trust owns those shares. This can help broaden access to asset building opportunities.

Finally, there are ways that other stakeholders — those self-identified and those we want to engage in this work — can support low- and moderate-income asset building through ESOPs. In our full report we talk about several stakeholders, but here will focus on two, philanthropy and community advocates:

- Philanthropy Large national philanthropies, along with their local family and community counterparts, can play an important role in three ways. First, they can spread knowledge about ESOPs to employers and community players. They can make opportunities for employee ownership more broadly visible and understood within communities where there remain existing privately-held companies — particularly in those communities where the firms employ significant numbers of women and/or people of color. Second, philanthropy might consider the development of an ESOP investment fund through a combination of philanthropic actors, or through a program-related investment model. The goal would be to increase the ease and accessibility of ESOP conversions from retiring business owners. Third, foundations can contribute to an education and training fund to help ESOPs structure the transition of their organizations in participatory ways, and to support new ownership training.

- Community Advocates Increasingly, community players are involved in finding ways to stem the tide of industry and job loss in communities. The more they proactively approach business owners and educate residents about the opportunities ESOPs present, the more likely that asset building opportunities will be retained or grow in their community. Community advocates may include employees, but it also means that Community Development Corporations (CDCs), Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFIs), Community Action Programs (CAPs), agencies, chambers of commerce, regional and economic development offices, and other local actors can become engaged. Labor unions and workers centers, too, are recognizing employee ownership as a path for enhancing worker empowerment and job security. Similar to the roles of philanthropy noted above, community players need to build awareness of employee ownership, and begin proactively educating their communities to develop an early warning system of businesses that may be likely to transition due to aging owners or other markers. They can also begin a process of new ownership training preparedness, similar to homeownership counseling, so that working people in communities are made aware of the steps and finances of such a transition. In this way both workers and businesses can act more proactively to retain the assets of the community.

A new frontier

Our study provides a successful proof of concept and opens up a new frontier for fighting wealth inequality through employee ownership. It demonstrates that each of the key stakeholders — employees through education and investment, managers through organizational practices at the site of work, and the private and public sector through policy that affects investments and performance — together can produce productive and efficient workplaces while simultaneously building the asset wealth of low- and moderate-income earners.

Cooperatives and ESOPs as shared capital organizations can learn a lot from each other and, together, can fight wealth inequality. ESOPs provide an important path for workers — especially those who are low-income and low-skilled — to become owners without drawing on their own limited savings or depleting low-income flows. Cooperatives are increasingly working to identify ways to preserve the assets of their potential members along similar lines. Both business models provide greater job stability and security to the workforce, and most examples of both provide greater opportunities for education and training targeted toward employee advancement and leadership than non-capital share enterprises. Cooperatives by structure can help reduce racial and ethnic wealth gaps more effectively than ESOPs, unless the latter are able to adjust the compensation formula, while both advance intergenerational transfers of wealth.

Work can and should ensure economic and social stability and greater opportunities and well-being for families.

It is critical to note, in summary, that new structures of work and relations to the workplace do not preclude the opportunity for everyone to build wealth through work. Brick and mortar as well as gig-based businesses, service work and production can adopt the cooperative or ESOP business model. Work can and should ensure economic and social stability and greater opportunities and well-being for families. When work “works” for all employees, we have stronger, more stable, more secure and financially thriving communities.

Janet Boguslaw is Senior Lecturer and Senior Scientist, Institute on Assets and Social Policy, Heller School for Social Policy and Management, Brandeis University. She is also a Louis O. Kelso Fellow & Wawa Inc. Fellow, Institute for the Study of Employee Ownership and Profit Sharing at the Rutgers School of Management and Labor Relations, Rutgers University.

Lisa Schur is Professor and Chair, Department of Labor Studies and Employment Relations and the Program for Disability Research at Rutgers School of Management and Labor Relations, Rutgers University. She is also an Executive Fellow at The Institute for the Study of Employee Ownership and Profit Sharing at the Rutgers School of Management and Labor Relations, Rutgers University.