Summer 2019 – Staying Power

The Science of Cooperation

Psychology provides new insights into collective action

By Taylor Zachary Lange and Timothy Waring

The success of cooperative businesses depends crucially on the cooperation of its members. But this common sense fact hides an important truth: cooperation is never guaranteed. So, what drives cooperation? Behavioral research from psychology, economics and anthropology helps explain when and how cooperation flourishes, and gives us tools to nurture it. In this article, we review how behavioral science defines cooperation and we highlight three factors discovered from that research that influence how cooperation grows: reputation, social norms and rules. Cooperatives can use these factors to foster meaningful cooperation and build business success.

The behavioral science of cooperation

The behavioral sciences have studied the determinants of cooperation in humans and other animals for over 50 years.1 In everyday life “cooperation” is understood to mean lending assistance; behavioral scientists define cooperation as an action that benefits another or a group of others. Scientists define altruism as a special type of cooperation that also comes at a cost to oneself. Behavioral scientists study cooperation and altruism using a branch of mathematics called game theory,2 and with interactive experiments often called “games.” The central finding of this research is that because “free-riding” (or benefitting without contributing) is often possible, cooperation requires some form of support to become durable in the long term.

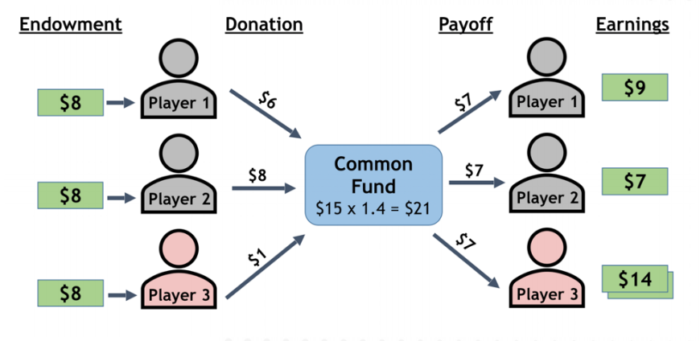

One of the “games” most applicable to cooperatives is called the public goods game. In a public goods game, a group of participants (players) optionally contribute to a common fund, from which they then all benefit equally. Contributions in this game are cooperative because they benefit others.3 Because contribution is optional, free-riding is possible. Figure 1 shows a public goods game4 in which free-riding pays off for Player 3.

Though the entire group benefits from high contributions, individuals who contribute nothing still benefit from the investment of others. The problem, of course, is that if everyone free-rides, there is no collective investment and therefore no public good.

A prominent example of free-riding in cooperatives can be found in the history of agricultural cooperatives, specifically before the formation of “New Generation” value-added cooperatives in the 1980s and 1990s.5 Previously, members of these cooperatives would sell their best harvest wherever prices were most favorable and then sell their less-desirable crops to the cooperatives because they were contractually obligated to purchase from members. The lack of desirable products caused these cooperatives to eventually close; free-riding behavior led to the demise of the public good that the cooperatives provided.

Cooperatives have found many different ways to manage the cooperation of their members and have formulated institutional structures that support it. Fields such as psychology,6 economics,7 and anthropology8 have also studied the conditions under which cooperative behavior can thrive and how free-riding can be minimized. Cooperatives can use these insights to reinforce the cooperation of their membership. In the rest of this article, we discuss three insights from the behavioral social sciences and suggest ways they might be utilized in the day-today operations of a cooperative business.

Experiments show that observable behavior drives future decisions.

Building cooperative reputations

Reputation is a powerful human motivator,9 and research shows that reputation can be used to nurture cooperation. Of course, a good reputation signals to other members of your organization that you are a reliable partner and a team player. So, allowing members to build a positive reputation around their contributions to the group is key. One way to build cooperative reputations is to make sure that cooperative behavior is openly observable by peers. The effect of observability on cooperation has seen extensive study.10 It shows that removing anonymity in public goods games increases the amount individuals tend to give. Experiments show that observable behavior drives future decisions; individuals in one experiment sought out information on their partner’s past actions when determining whether or not to help them. Those who were more cooperative in the past received more help than those who didn’t previously cooperate.11 This shows how reputation can allow cooperation to reward prior cooperation in a virtuous cycle.

Some examples of this come from blood-drive donations and support for National Parks. When a newsletter is distributed that shows who is on the blood donor list, more individuals tend to come forward and donate blood,12 and when a donation box for parks is placed in view of a ranger station, donations increase.13 And, of course, research in cooperatives suggests that the reputational effect of observable contributions can build trust,14 too. In many circumstances, making all cooperative actions observable is sufficient to encourage cooperation.

Cooperatives can utilize this information in a number of ways. The first is to make sure that key activities that require member cooperation are transparent in process and result. For example, if a cooperative grocer could benefit from longer work shifts, they might ask for longer shifts and display members’ work hours. This type of policy uses reputational concerns of cooperative members to avoid negative gossip and seek peer approval—both of which are punishments and rewards in and of themselves. One study of cooperatives specifically found that a cooperative restaurant with transparency in work schedules was able to control free-riding by utilizing informal peer pressure and transparent work expectations.15 Cooperative businesses could examine the day-to-day operations that require true cooperation (as defined by the public goods game) and consider if contributions are sufficiently transparent to build cooperative reputations.

Building cooperative social norms

Social norms are another powerful force that shapes human decision making.16 Cultures are composed of norms of behavior, language, etiquette and so on. People also have norms of cooperation for different circumstances. How much you cooperate with your sports team might be different than how much you cooperate with your neighbors, for instance. Moreover, we tend to adopt the norms of the society and organization we find ourselves in. This means that humans are conditionally cooperative: we cooperate only when others cooperate.

Experimental research bears this out. On the whole, individuals appear to be cooperative so long as they know that other people are being cooperative.17 Goldstein et al18 show that advertising what cooperative behavior looks like and that others are doing it can have significant effects on behavior. A majority of individuals give in amounts that are similar to others in their group if past information about their peers is known, and this pattern holds true in experiments in the lab,19 in the field20 and in real-world case studies.21 For example, people will reuse hotel towels 26 percent more often when they know that others have been doing so, a cooperative action that benefits the environment.22 Such cases show that people tend to conform and reciprocate the cooperation that is shown to be the norm, even if the rules don’t explicitly require cooperation. For example, our research laboratory played a cooperative game with shoppers at neighboring grocery stores—one cooperative, and one traditional. We found that people exiting the co-op were more generous (donated a larger portion of their experimental earnings to others) than shoppers at the traditional grocery store.23 This was true even when we accounted for differences in income, age and gender. The co-op we studied had stronger norms of cooperation, as most co-ops probably do.

Humans are conditionally cooperative: we cooperate only when others cooperate.

Sometimes cooperative norms require even more support, especially when a social norm needs to be changed. Another simple and powerful tool to support cooperative norms is reward (for cooperation) and punishment (for free-riding). Research shows that reward and punishment can make cooperative behavior flourish. Experiments that allow individuals to pay to penalize free-riders show that punishment gradually decreases over time and cooperation slowly increases to a sustainable majority.24 Rand et al25 also found that individuals donated even more if positive reinforcement is available. Experiments of this type show that individuals tend to act cooperatively when there is a firm but fair system in place, rewarding good behavior and punishing bad. And punishments for free-riding needn’t be harsh: a cooperative will benefit more from a reformed free-rider than an expelled one.

Rules take on a different role when considered as tools to bolster cooperative behavior, rather than coerce or require certain outcomes.

For cooperatives, cultivating social norms of cooperation is essential when it is not formally required by some institutional mechanism. Cultivating norms can also be a stepping-stone to more formal rule structures. Establishing common behavior patterns is difficult, but if new and existing members can see that cooperation is the norm, they will tend to emulate it.

Building rules to reinforce cooperation

All cooperatives rely on rules to organize their business, and for good reason. Informal norms of cooperation are insufficient to make a durable business, no matter how observable. Rules are commonplace and common sense. But rules take on a different role when considered as tools to bolster cooperative behavior, rather than coerce or require certain outcomes. A classic finding from behavioral science is that rules can relieve individual members of the onus to punish free-riders,26 placing responsibility on the organization as a whole and allowing punishment to be more just and transparent. Rules can pick up where norms and reputation leave off. But which rules?

While there is no perfect guide to which rules fit a given business or organization, rulemaking — especially democratic rule making—creates a concrete social contract that can formalize cooperative social norms. Of course, democratic rule making is common in cooperatives, and fosters a sense of ownership over the rule structure. Scientists have found that democratically agreed upon rules increase cooperation. In one experiment, participants were subjected to a two-person cooperative dilemma called the Prisoner’s Dilemma. After one round, they could either vote to impose penalties on people who did not contribute, or choose to have penalties imposed by the researchers.27 Participants who voted on the penalties (my rule) cooperated nearly twice as much as when the penalty was externally imposed by an outside force (just a rule). A related experiment found that when individuals agree upon and consent to punishment mechanisms for free riding, cooperative donations increase.28

One interesting example of the role rule making plays in cooperatives comes from the weaver cooperatives in Rochdale, England, who in 1844 wrote down a set of rules to improve their business. The rules were first established in part because early cooperatives allowed members to trade on credit. When overuse of credit led to overwhelming debt, the founders created new rules that required business to be conducted in cash.29 The rules were successful and evolved into what we know today as the 7 Cooperative Principles. Our research30 shows how those cooperative principles have accumulated and changed over time, and how they have made a huge impact on the cooperative movement.

Cultivating internal cooperation

Research on cooperation can be of great value for cooperatives. In this article, we have outlined three specific insights from behavioral social science: building reputation through observability, cultivating cooperative norms, and creating rules to institutionalize cooperative behavior. Each of these insights can help cooperatives cultivate cooperation internally. Furthermore, these are just three of many such insights to come from the science of cooperation. It is our hope that such research can help cooperatives better build more successful, equitable and sustainable enterprises.

Taylor Lange is a PhD candidate at the University of Maine in Ecology and Environmental Science focusing on common pool resource management and cooperation science. His research explores how small food buying clubs in New England cooperate and how they succeed. You can email Taylor at taylor.z.lange@maine.edu.

Timothy Waring is an associate professor in the School of Economics and the Mitchell Center for Sustainability Solutions at the University of Maine. He studies how cooperation influences social change and environmental sustainability. His new research concerns the role of behavioral cooperation in cooperative organizations.