Fall 2020 – Building Diversity, Equity and Inclusion

Diversity in Governance

A cooperative model for deeper, more meaningful impact

By Karen Miner and Sonja Novkovic

There is a convergence of ideas around redefining the purpose of both enterprises and the broader economy. The rhetoric has become ubiquitous— from the Davos 2020 “Sustainability Manifesto”1 and the U.S. Business Roundtable’s Statement on the Purpose of a Corporation to conscious capitalism, “for purpose” enterprise and the circular economy. That being said, it is difficult to imagine how the corporate model of business would be capable of sufficient transformation to deliver truly sustainable outcomes, since the fundamental purpose of ownership, control and benefit is tied to investment (e.g. financial return on capital).

On the other hand, the cooperative business model is compatible with the most progressive understanding of sustainability, but many cooperatives still need to broaden their view toward deeper and more meaningful impact. This requires sophisticated and systematic adherence to the cooperative enterprise model in order to enable transformation from an economistic to a humanistic paradigm and from purely financially-motivated enterprise to alignment with the 7 Cooperative Principles, as expressed in the International Cooperative Alliance (ICA)’s Statement on the Cooperative Identity (referred to as ICA Statement throughout).4

In the world of cooperative research and practice, we talk about co-ops as if they are all made equal. Although the saying “Once you’ve seen one co-op, you’ve seen one co-op” has become something of a mantra in the movement, we continue to talk about cooperatives as one homogeneous enterprise model. Partly, this is due to the unifying ICA Statement—to which the global cooperative movement subscribed in its latest iteration in 1995—but it can also be attributed to democratic governance as a common feature.

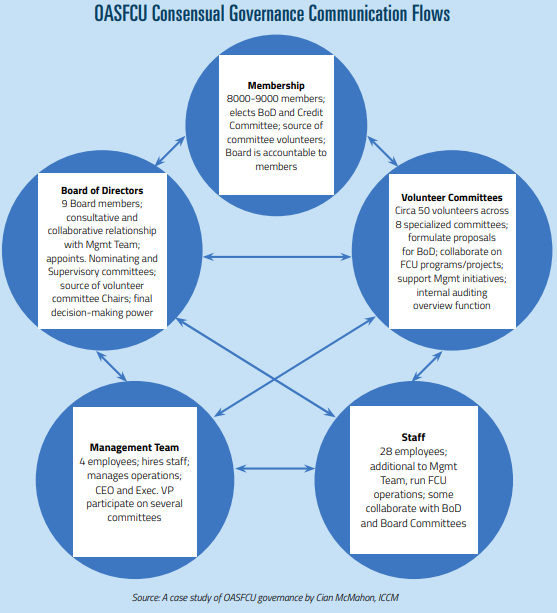

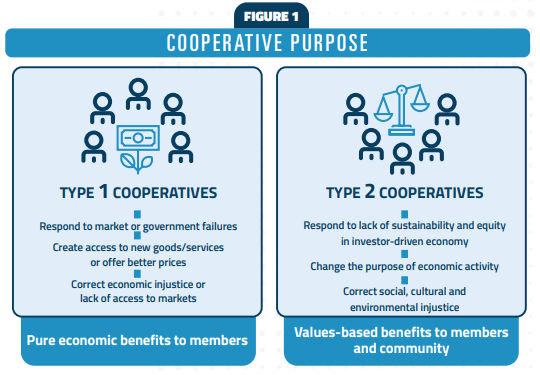

While all cooperatives are member focused and democratically run, what that means and how it is applied varies widely, depending on context. The enterprise model and organizational purpose (purpose of membership) influence the type of cooperative (see Type 1 and 2 in Figure 1) and the resulting democratic governance structures (control through to collaboration). In this article, we elaborate on Type 2 cooperatives and discuss diversity (as opposed to homogeneity) in membership, humanism in management and governance (not “economism”), member-centricity (not investor), broader external environment, and big picture context (long-term, community and environment). In closing, we illustrate some aspects of humanistic governance by the OAS Federal Credit Union’s participatory structures that are driven by a humanistic approach and values-based purpose.

Building blocks of the cooperative enterprise model

Building blocks of the cooperative enterprise model

Regarding organizational purpose, cooperative “ideal type” has two interpretations in the literature. Type 1 provides pure economic benefit to members, while Type 2 captures the essence of the ICA Statement. Although the reality is more complex than either ideal type, placing a cooperative in one or the other of these categories clarifies the foundational elements of purpose, values and principles as the critical aspects of the cooperative enterprise model (see Box 1). For example, some credit unions will focus on economic benefit to members (Type 1) while others will move deeply into Type 2 territory (redefining wealth, defining its purpose as vehicles for community and economic development). The same dichotomy can be observed in other sectors (e.g. food, agriculture, electric).

The economic benefit interpretation (Type 1) dominates the neoclassical and new-institutional economics view, as well as some legal definitions. The stress there, besides the cooperative’s objective to address “market failure,” is on the property rights of members and an investor logic. The advantage of cooperation—particularly when members are small businesses or self-employed—is seen to be in the economies of scale reflected as either lower costs of inputs, or increased prices for outputs earned through market pricing and patronage dividends, or possibly value-added production process. For worker cooperatives, the incentive to form a Type 1 cooperative is in average income increasing with a share in profit distributed to workers, according to this view. In addition, favorable regulatory frameworks or fiscal incentives may induce cooperative formation.

Type 2 cooperatives take the much broader view reflected in the ICA Statement and implicate economic, social, environmental or cultural motivations for cooperative formation, as enterprises embody the ethical values of their founders in a collectively owned and controlled enterprise. The global cooperative movement subscribes to this definition, as do the United Nations’ (UN) agencies. The International Labour Organization’s Promotion of Cooperatives Recommendation (No. 193, 2002) adopts the ICA Statement in its entirety. This was also the basis for the UN’s proclamation of the 2012 International Year of Cooperatives, and is the interpretation of a cooperative enterprise we adopt in this article.

Adhering to cooperative identity implies a deliberate choice of an ethically-grounded enterprise reflecting solidarity among its members. This is typically the practice of cooperatives that build the social and economic resilience of communities; focus on creating well-being including, but not limited to, financial benefit; serve as agents for social and economic transformation; and pursue explicit social, economic and environmental objectives.

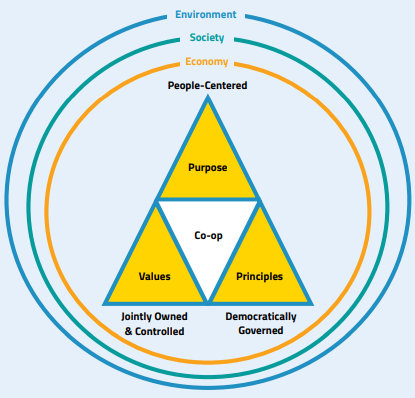

The ICA Statement has a deeper meaning, beyond a one-dimensional sketch of a cooperative enterprise. When taken apart, it uncovers purpose, values and principles, along with three building blocks of the cooperative enterprise model: people-centered , jointly owned and controlled, and democratically governed. Taken together, these properties inform business practices, as well as organizational structures; incentivize organizational behavior that is markedly different from capital, state and nonprofit entities; and frame the purpose and nature of the cooperative enterprise as a values based business (see figure within Box 1).

Governance

The governance system of the cooperative enterprise can also be understood differently, either as a principal-agent problem, a humanistic model, or a combination of the two. Under agency, members are represented by the board of directors who hire professional managers to run the enterprise. Due to the separation between ownership and control and managerial opportunism—an assumption about human behavior shared with the view of investor-owned businesses—a primary role of the board is to hire, manage and monitor the CEO to ensure that the enterprise operates in concert with member interests. The more homogeneous (less diverse) the members, the easier and less costly it is for the board to represent them.

Under the humanistic paradigm, on the other hand, member representatives (e.g. board) and managers are viewed as stewards of the enterprise, and consider multiple stakeholders in their decisions. Diversity is lauded in this case (Turnbull 2002) because human beings have limited cognitive abilities to process and store information. The more diverse voices are at the table, the better information sharing and processing capacity, and better governance. And, governance structures are more diverse, moving beyond the concept of only an apex board toward a system of board(s), committees and councils that engage more members and stakeholders in decision-making.

Some call for a balance between the principal-agent and humanistic approaches as paradoxical forces are at play in organizations, including cooperatives. While seemingly at the opposite ends of the spectrum, both control and collaboration between management, members and other stakeholders are required for effective leadership, it is argued. In a similar vein, cooperatives are seen to deploy both democracy and hierarchy; while regarding their members’ motivations, they seek both individual and collective benefit; and pursue social and economic goals.

The cooperative enterprise model is a trifecta of purpose, values and principles coupled with three fundamental properties inherent in cooperatives as peoples’ organizations (people-centered, jointly-owned and controlled, democratically governed). These three properties, when operationalized, form the building blocks of the cooperative advantage in the context of increased complexity:

The cooperative enterprise model is a trifecta of purpose, values and principles coupled with three fundamental properties inherent in cooperatives as peoples’ organizations (people-centered, jointly-owned and controlled, democratically governed). These three properties, when operationalized, form the building blocks of the cooperative advantage in the context of increased complexity:

People-centred (as opposed to capital-centred) governance and management assumes people are intrinsically motivated social beings, balancing their personal and group interests in accordance with general moral principles. Organizations, in this view, embrace a balance of objectives (including financial), and tend to involve key stakeholders in their decision-making process.

Joint ownership and control (distributed, rather than concentrated) is a hallmark of cooperative organizations, and it is intertwined with members as owners, controllers and beneficiaries. Although typically operating under private property regimes, cooperatives distribute ownership rights equally among their members and may hold a part of their assets in non-divisible reserves.

Democratic governance is based on one member, one vote (rather than wealth-based). Self-governance is the underlying engine of autonomous cooperative enterprises, with the vital component being democratic decision-making by their members. Decision-making practices in cooperatives depend on the purpose of the organization, and wider context.

Realizing that cooperative members collectively own and control the enterprise as its patrons (or workers); democratically govern with voting as a personal right, rather than based on capital shares; and subscribe to social and economic justice through cooperative values and purpose, governance systems need to match this underlying enterprise structure. Misalignment between the two results in discrepancies in the organization’s strategy, as well as CEO motivations,leading to isomorphism and an increasing risk of the cooperative’s potential demise.

A case for diversity: humanism, members and society at a crossroads

Assumptions of humanistic theories in economics and business are more suitable for peoplecentered cooperative enterprises. Capital plays an instrumental but subordinate role, reflected in voting as a personal right of members, rather than a property right. When this rule is altered, such as in some producer cooperatives, it is altered by the volume of patronage—critical for the coop’s survival and success. This is an indication of membership as a user-relationship, rather than investor (see more on this below).

Humanism and governance of cooperative enterprises

Humanism and governance of cooperative enterprises

Humanistic economics and humanistic management theories put people first, arguing that the purpose of economic activity and institutions needs to shift from its current focus on wealth maximization, to increasing wellbeing and promoting human dignity.

As self-help organizations formed to attend to the needs of their members, cooperatives fit well with the humanistic paradigm, as they address socioeconomic injustice and structural imbalances in the economy. Worker cooperatives are the benchmark model in humanistic economics, while other types of cooperation express the need to extend promotion of human dignity beyond the realm of work into all aspects of economic life.

Cooperatives come together to address questions of ethical principles and values, with a model of enterprise that relies on members’ vision and democratic participation. There is a point of view and some evidence that most cooperatives (including Type 1), have good reasons to provide conditions for humanistic governance. The paradox view notwithstanding, the usership relationship ought to prevail. As Crombie points out, “Overall, the evidence suggests that mutuals are likely to use collaborative governance systems, whereas corporations are more likely to use controlling systems.”

Further, there is evidence that members of producer cooperatives, although facing a significant economic risk, deal with a cooperative on the basis of social commitment, rather than purely economic drive. Members engage in governance, patronage, committee work, financing and other forms of participation as a result of affective and normative commitment, and not purely on financial grounds. Therefore, to impose an agency-relationship between cooperative boards and managers may result in a self-fulfilling prophecy with reduced trust and increased opportunistic behavior. The potential risk of oligarchy (too much power given to the CEO) needs to be resolved with appropriate governance architecture.

The member dimension: ownership, control and benefit. Members are the foundation and heart of all cooperative enterprises as it relates to ownership, control and benefit. The multi-dimensional characterization of a member is an essential aspect of the enterprise model; a cooperative’s approach to this member relationship determines the strength of a shared commitment and common purpose underlying membership.

Related to all three elements of membership, their motivations to join a cooperative (sketched above as Type 1 or 2) will influence and ultimately dictate the way that the enterprise is governed and managed. Why a member joins a cooperative will also determine what types of democratic structures are put in place to represent and protect member interests.

The type of membership will have a profound impact on members’ concerns, which will be reflected in the governance and management structures and processes. Worker-members—insiders to the firm—typically care about fair income distribution, job sharing, non-hierarchical power structures and conflict resolution mechanisms. Producer-members may care about equity and fair supply mechanisms, prices, risk mitigation and supply management. Consumer-member motivations vary, from access to necessities and protection from market fluctuations (housing cooperatives are one example), to access to ethical products, and local development.

Members jointly own, control and benefit from the cooperative, and engage with the enterprise as workers, consumers or producers. However, members “wear many hats.” Besides their primary type of engagement and patronage, the responsibility of membership includes participation in governance, capitalization of the enterprise, and other forms of support. Membership is a complex set of relationships that affect every facet of the cooperative.

Multi-stakeholder cooperatives (MSC), also called solidarity cooperatives, integrate multiple types of members into cooperative ownership, management and governance. This added heterogeneity and diversity in governance structures is thought to be costly and unsustainable, yet in practice this model is quite prevalent, both as a legal form in some regions, and as a practice where laws do not prescribe membership type. Engaging multiple stakeholders in setting the vision, and in the decisionmaking, is a feature of humanistic governance systems. Generally speaking, individual members also simultaneously belong to multiple categories of users of the cooperative: as workers, consumers, suppliers and community members. Therefore, there is more to multi-stakeholder management and governance than the transaction costs economic literature would suggest, particularly with regards to motivations for MSC ownership and control. Solidarity is at the root of social relationships in most MSCs; a common purpose ensures MSC longevity. Lund calls this feature “solidarity as a business model,” arguing that stakeholders in MSCs build long-term relationships to encourage transformation, rather than engage in purely transactional relations.

These lofty expectations of membership in a cooperative certainly benefit from diverse perspectives. The question, of course, is how to manage diversity to ensure that each different voice is not pulling the cooperative in a different direction. The answer, at least in part, seems to be the shared purpose of the enterprise. As long as members share the vision and the purpose of their cooperative, diversity may be an asset, rather than a cost. Therefore, establishing a clear understanding of the cooperative purpose and adapting to evolving members’ needs is the governance priority—a task that must be revisited on a regular basis. How cooperatives do that depends on the context.

Democratic governance and the cooperative enterprise

T he ICA’s Cooperative Principles and Values (ICA, 2015) suggest that cooperatives institute participatory forms of democracy in their organizational governance and management that respect and promote human dignity, democratic decision-making, and engagement of members, employees and other key stakeholders. Further, those members engaged in governance activities focus on total value creation and equitable distribution of benefit. Governance of cooperatives is both inseparable and integrated within the enterprise model (see Box 1). As is consistent with our overall framing of the enterprise model as context specific, cooperative governance must push back against a onesize-fits-all view of the cooperative or corporate governance models, as the best models evolve and are dependent on the cooperative type, size, culture, country, sector, economic and other factors. The governance system, as a component of the enterprise model, is built around structures, processes and dynamics that experiment with and/ or fully embrace member-centricity, participation, engagement and democracy.

Structures will be impacted by the organization’s purpose and members’ relationship with the cooperative. Different factors will shape formal governance structures, including the nature of ownership and control, the type of governance bodies, and formal rules and policies.

Processes are defined as the way strategic directionsetting and control is carried out. They are democratic and participative in well-functioning cooperatives, but context dependent and not uniform. What that means and how it may be executed is contingent on the type of members, and whether members are involved in the operations (insiders, such as in worker and housing coops), or external to the organization. Further, the size of the cooperative and stage in its lifecycle will influence the processes.

Dynamics refer to the changing nature (adaptation and evolution) of structures and processes over time, due to evolving internal and external factors influencing members’ needs and goals. As an example, the external environment can call into question the original raison d’être of the cooperative, thus requiring a proactive approach to organizational change, rather than as a response to crises brought on by competition, changing consumer behavior, economic turmoil, etc.

When we consider this governance system, some cooperatives are exemplary in their adaptation of governance to fit the enterprise model, while others lean into conventional corporate governance approaches designed for investor-owned corporate models. It is important to be knowledgeable about the differences to ensure that wise choices are made and a strong cooperative enterprise is enabled.

The big picture

Beyond the variability in cooperative business context, we must also situate ourselves in the current social and economic context. This creates an important opportunity for the cooperative movement and business model. As we have collectively become acutely aware of the planetary boundaries and shortfalls in the provision of basic necessities—and reminded of it by the fallout of the COVID-19 global pandemic—this is the time for all cooperatives to live up to the expectations set by the ICA Statement. This requires a collective effort to promote, develop and enhance Type 2 cooperatives, including motivating changes within cooperatives that have been focused purely on financial gain to members. Social-ecological purpose and financial benefit are not separable, nor is there a trade-off between the two in values-based cooperatives.

Members’ motivations to establish a cooperative may have been different decades ago, but a cooperative enterprise today must promise social justice, equity, equality and reflect the society in which it operates. Governance systems need to reflect this changing reality: cooperative leaders cannot afford to wait and see when their members will notice the changes around them, but must provide vision and direction as to where they need to go to “do the right thing.” Economic paradigms are changing, and are more aligned with the ICA Statement than they have ever been. Cooperatives have the potential to instigate transformative change as they rest on a different (not-for-profit and people-centered) logic; they address the structural causes of inequality and social injustice, which are the root causes of contemporary development issues. However, larger, more mature cooperatives are prone to isomorphism as conditions around them change. In order to serve their members in these new social and economic circumstances, cooperatives need to stay in touch with member and community needs and find purpose in protecting member vulnerabilities. Deep forms of member participation, engagement and social innovation are key elements of success in so doing.

Cooperative members rise to the occasion in a crisis, forming cooperatives where needs arise, in a self-help effort to resolve the issues as they have been doing for centuries. But in order to remain relevant and fulfill the vision outlined in the Blueprint for the Cooperative Decade (2013), current and future cooperative enterprises need to find a way to fit into and contribute to the big picture. The path to success involves cooperatives with complex purposes and accompanying humanistic management and governance systems.

Since 2003, the International Centre for Cooperative Management (ICCM) at Saint Mary’s University has provided leadership in cooperative management and governance. Sonja Novkovic and Karen Miner are particularly focused on cooperative governance and are collaborating on a research project through 2022 with colleagues at the Katholieke Universiteit Leuven (KU Leuven) with the funding support from FWO Belgium (SBO project S006019N). Learn more at managementstudies.coop.

Sonja Novkovic is a Professor of Economics and Academic Director of the International Centre for Cooperative Management at Saint Mary’s University. She is a member of NCBA CLUSA’s Council of Cooperative Economists and a regular contributor to the Cooperative Business Journal. Email her at snovkovic@smu.ca.

Karen Miner is the Managing Director, Governance Researcher and Adjunct Professor with the International Centre for Co-operative Management at Saint Mary’s University, where she works with cooperative and credit union professionals from around the world. Email her at karen.miner@smu.ca.